‘I was at breaking point’: With no family to turn to, leaving children’s home tough for some youths

Nearly 600 children and youths live in residential and youth homes in Singapore. What happens when they must live independently? Social service providers tell CNA Insider what more can be done to ease the transition for the vulnerable.

An average of 15 youths are discharged from residential and youth homes into independent living each year, the MSF said. (Photo: iStock/FotoDuets)

SINGAPORE: At age four, he was placed in a residential home for children who had been neglected or abused.

James (not his real name) lived there until he was 18, when he had to move out.

He had started thinking about this day when he was 16 and had discussed it with his social worker in Melrose Home. His aunt agreed to take him in.

The transition turned out to be “too fast” and “quite tough”, and the living arrangement broke down.

His aunt lived in a four-room flat already occupied by four people. James slept in the living room. Without a sense of personal space, he felt “kind of naked”.

There was also tension: A household member made James feel he was “a burden”. “He didn’t have to say it; I could sense it,” said James, now 22, who asked not to be named.

By the third month, his living situation began to feel untenable. But there was nowhere else to go.

He earned about S$1,000 a month by working part-time in the food and beverage industry. His personal monthly expenses amounted to S$600 to S$700, while he chipped in S$50 to S$100 for household expenses. Polytechnic fees cost him S$400 to S$500 per semester.

It took about nine months to find an alternative: His girlfriend was living with her grandparents in a rented flat and had space for him — just when “I was at breaking point”, James recounted.

But trying to support himself while pursuing a diploma proved too much. “I had to think of money constantly. I had to plan ahead,” he said. If he did not get the shifts he wanted at work, for instance, he would “lose out on money and have to plan again”.

“All this kept repeating. Then the poly workload came, so I had to juggle. It was super messy,” he said.

Groupwork for school projects often happened on Saturdays, when he had to work. He would tell his colleagues he was taking a toilet break, then join his project mates nearby for 15 minutes. When he returned, colleagues would ask why he had taken so long.

“Sometimes I’d do (project work) during my break time, (but) I’d be super exhausted,” he said.

During that period, “almost every day was a bad day”, he said. “It’s like I’m half awake the whole time, so I’d just drag (myself) through the day.”

He got a grade point average of 0.8 in his first year at polytechnic and dropped out.

AN ‘ANXIETY-PROVOKING’ PROCESS

Placement in a residential home is meant to be a temporary arrangement for those who have been neglected or abused by their parents or carers. There are 21 licensed residential homes in Singapore and two Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF)-operated youth homes.

As at the end of last year, close to 600 children and youths were living in these homes, a ministry spokesperson said.

Many children manage, over time, to safely reintegrate with their families.

But some have no family or kin to return to as they approach the homes’ general age ceiling of 21. An average of 15 youths are discharged from residential and youth homes into independent living each year, the MSF said.

For these youths, the next step is a leap — into a world where they must fend for themselves.

This transition can be fraught with anxiety and challenges, say social work professionals, who believe more can be done to ease the process.

“It’s actually quite a big jump — from (a residential) home where there’s easy access to staff for help, to (having) completely no one,” said Soh Ying Si, deputy manager of the social care team at Melrose Home, which is run by the charity, Children’s Aid Society.

At that age, youths may not have finished their education but need income and a place to live.

Finding accommodation is often the first challenge. The youths generally cannot afford to pay market-rate rent for a room. They do not qualify for public rental flats if they are unmarried or have no children; applicants must be at least 35 years old under the Joint Singles Scheme.

Then there is the search for good, long-term employment opportunities. “Because if you’re living independently, you have to have a source of income,” said Cindy Ng-Tay, Melrose Home’s director.

Youths who are still studying will need part-time employment that enables them to complete their education, she said.

The youths also need a support network. For their peers with families, this typically means having “adults who’d give you advice, who’ll bail you out when you make poor decisions, who’ll give you that financial buffer when you need it, who’ll give you emotional support when you start going through developmental milestones”.

“These kids don’t have that kind of backing. So they’re very frightened, even though they may look macho,” she said. “Transitions are more anxiety-provoking (for them).”

The youths’ past experience of neglect or abuse sets them “a few steps backwards” and must also be taken into account, she said. “Have they overcome their trauma history? Can they self-manage to (the) point (where) they can take care of themselves?”

FACING REALITY

“Reality” was a word that often came up during interviews for this story.

There was the reality of life in a residential home, and youths coming to grips with the reality that they were unlike their peers who live with families and need not worry about housing or taking on part-time work while studying, who could stay out late and spend on things like concert tickets.

Raymond Low remembers being taken by his mother to Chen Su Lan Methodist Children’s Home (CSLMCH) at the age of six. “I felt lost, I felt overwhelmed at first,” he said.

It was such a big place and not the usual home (I knew). When she left, reality slowly started to (sink) in, and I knew somehow, roughly, that my mum had left me.”

He cannot remember whether he cried. “Most people will cry (on their) first night; it’s like a ritual,” he said.

But the residential care officers were “very nurturing”, and he felt more comforted.

“It helped that there were a lot of other children there, so I was distracted by the games and all that,” recalled the 25-year-old, who lived at the home until he was 18.

He participated in the daily programmes and saw his mother at weekends. “Slowly you get used to the routine, and I adapted quite well,” said Raymond, whose three siblings joined him in the home a year or two later.

In residential homes, the process to build a child up starts early. Then there are the efforts of staff to get the youths ready — as ready as they can be — for the real world once they are on their own.

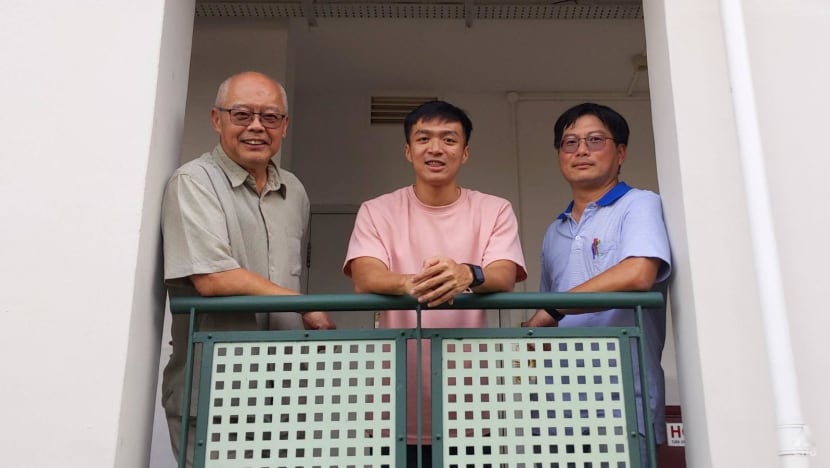

In CSLMCH, residents have access to therapy, academic help and enrichment programmes, said executive director Low Kee Hong. These are services the home can offer because of fund-raising efforts that supplement government funding.

The children live in groups of 10 to 15 in dormitories equipped with a living room, kitchenette and bedrooms. Each dorm is typically staffed by two live-in residential care officers.

“We’re no longer a room-and-board home. Today, we provide many professional services for the children to restore … their lives with new perspectives and opportunities,” said Low.

The home also hires its own cleaners, cooks and other support staff, which means the children are surrounded by familiar, safe and caring persons, said Low. At last year’s Christmas get-together, two members of the support team were voted the children’s favourite persons in the home, he shared.

In Melrose Home, Melrose Heroes is a one-year life skills programme adapted for residents of various ages. They learn about themselves as well as personal safety. Older children learn about personal finance and preparing for employment.

Like CSLMCH, Melrose raises funds to hire more social workers and residential care staff as well as provide services such as therapy, Melrose Heroes, academic tuition and other activities.

More support is given in the lead-up to the youths’ discharge — and afterwards, known as post-care. Homes say they also raise their own funds to help youths who have been discharged.

CSLMCH’s family care team journeys with youths for several years after their discharge, said Low. This could be through monthly phone or video calls, meeting up or even going to receive those who are discharged from reformative training.

The home also helps to connect some needy youths to churches for assistance and sponsorship. Donors help with living expenses and education, while the home follows up by monitoring the youths, ensuring they are accountable every semester, said Low.

Raymond, for example, recently graduated in chemical engineering from the National University of Singapore with CSLMCH paying the first two years of his university fees and a donor sponsoring the next two years. He also received S$300 a month pocket money and supplemented it by giving tuition.

“It’s always about facing reality and facing yourself, taking hold of your life and putting a shine into the future. That’s our goal for every child, regardless of age,” said Low.

Melrose’s youths who “age out” are connected to family service centres and other community resources by the home’s social workers.

This can be “quite intense” as the youths can be anxious, so a social worker could be meeting up with a discharged youth almost weekly for about six months and accompanying the youth to the first few sessions with the family service centre’s staff, said Ng-Tay.

To give Melrose’s youths a better foundation before they are “launched into the community”, as she puts it, the home started the two- to three-year Independent Living Programme last July.

It aims to equip Melrose’s youths aged 17 and above to be self-sufficient, responsible for themselves and able to make independent decisions.

Eight youths — seven current male residents and James — make up the inaugural batch. Cooking lessons are ongoing, and the boys have had a session on identifying career aspirations and longer-term planning.

They have had a financial planner explain savings, the Central Provident Fund, insurance, investments and taxes over three sessions and a real estate firm explain the do’s and don’ts for renting a place.

For four of the youths with no families to return to, social workers will journey with them as they search for a place to rent. The programme will cover their housing expenses including rent and utilities, with the youths contributing a sum they can afford, said Ng-Tay.

Property developer CapitaLand is sponsoring the first year of the programme.

The housing component came about because the boys said they wanted to live together after leaving the home, probably to save money and because they were “quite close” friends, said Soh.

For her and her colleague Aiswarya Ajith, seeing the youths look out for one another was heart-warming.

When viewing a unit with an oddly shaped room, James dismissed the idea of having a bunk bed because the upper bunk would be too uncomfortable, even though another boy was willing to sleep there. “They’re not selfish … even though they like to bicker,” said Soh.

On a trip to Ikea to check out furniture prices, the four boys contemplated doing without bed frames and squeezing around a dining table in lieu of buying study tables.

“We took them to Ikea (and) Harvey Norman (to expose) them to reality, also to teach (them) how to prioritise what they need,” Soh said.

The red-hot property market, however, gave rise to anxiety. One unit they viewed was snapped up by another party less than an hour later, while another landlord decided to rent to a family instead of four boys, said Soh.

This led them to ask, “What if, six months down the road, we still can’t find a flat? What’s going to happen to us?”

The “constant worry” as she journeys with the boys is the hardest part, said Aiswarya. “Will they be okay by themselves?”

MINISTRY WILL CONTINUE TO REVIEW SUPPORT

In reply to CNA Insider’s queries, the MSF said it is committed to supporting children and young persons who are unable to be reintegrated with their families or kin despite the efforts of all parties.

Social service professionals will prepare the youths for independent living about six months prior to their discharge, a spokesperson said. The youths will be connected to family service centres for post-discharge support to smoothen the transition from home to community.

They will be referred to social service offices if they need financial assistance or employment support. They may also be connected to community befrienders and mentors.

Youths who continue tertiary education after discharge can apply for government bursaries and school-administered financial aid to manage their fees and related expenses at publicly funded institutes of higher learning, the MSF said. “They can approach their institution’s financial aid office for assistance and advice on the financing options available.”

For those who need housing, social service professionals can facilitate referrals to hostels, rental or other housing options, the spokesperson said. Some residential homes allow youths to continue their stay, while others provide additional financial support and check in regularly with the youths, she added.

The MSF said it will continue to review the support for youths after their discharge from state care. Members of the public who are keen to support disadvantaged youths or other social causes can join the MSFCare Network (go.gov.sg/msfcarenetwork) as volunteers, it added.

‘WE’LL GIVE THEM OUR BEST SHOT’

Nonetheless, many youths ageing out of residential homes could do with more access to affordable housing in the community besides some financial assistance while they find their feet, social service professionals said.

Access to affordable mental health resources would also be beneficial, as would a dedicated mentor.

“What will really help is a dedicated mentor, someone you see as a big brother or sister,” said Raymond, who kept in touch with two staff members of CSLMCH after he left.

“(A mentor) can keep you accountable (and be) someone you can lean on, (who’ll) walk with you and help you process … the past and the emotional struggles.”

He lives with his mother now, along with his siblings. When he left CSLMCH in 2016, he was excited but also apprehensive as they all would be living together for the first time in over a decade.

Growing up in a residential home, he also felt insecure about making close friends at school for fear that they would treat him differently if they knew his background, he said.

It was only this year when he overcame many of his reservations and saw his family “in a different light”. “I really wanted to be close to them and really wanted to protect this family,” he said. The change has made him feel “a lot lighter”.

Youths should not feel alone in a period of transition and in their search for solutions to challenges, agreed Yeo Bee Lian, director of services and programmes at social service agency Trybe, which manages the Singapore Boys’ Hostel.

In 2016, Trybe started the Growing Resilient Youth-in-Transition (GRYT) programme to provide post-care support for youths discharged from the Boys’ Hostel. Last year, GRYT began taking referrals from other children’s homes and has youths from four to five homes under its wing.

The youths are referred at least three months before their discharge. A social worker is assigned to befriend and build a rapport with the individual and identify the goals and areas of support he or she would like during the transition, said Yeo.

The social workers follow up on the youths for 12 to 15 months after their discharge and connect them with community resources they can tap.

Trybe set up GRYT after noticing that some youths wished to keep in contact and for some form of support after they leave the Boys’ Hostel, said Yeo. “We also noticed a group that made very good progress when they were in care but were unable to sustain it very soon after their discharge.”

The situation is “not so straightforward” that those who do well in residential homes would fare equally well on their own — hence Trybe’s structured programme.

To ramp up support for youths ageing out of residential homes, the charities must raise more funds.

GRYT’s pilot run was funded by the National Council of Social Service, said Yeo. It is also a charitable cause supported by the Community Foundation of Singapore, and Trybe is looking to raise funds for the programme through corporates and other means.

CSLMCH is running a fund-raising campaign for its education and enrichment fund.

The Children’s Aid Society, meanwhile, is redeveloping Melrose Home at its Clementi Road site as the former building had an asbestos issue. Asbestos is a building material used in the past that poses serious health risks.

Melrose’s temporary site is on Boon Lay Avenue. The new home, dubbed Melrose Village, will be key to providing better care for children and youths, said Children’s Aid Society executive director Alvin Goh.

The plan is to carve out space for its youths who are about 18 but without sufficient self-management skills for reasons such as a more traumatic past. “We’ll give them our best shot,” said Ng-Tay.

“If we have time with them, it’s only until (they’re) 21, so we’ll do our best in that space to teach them independent living skills.”

Melrose Village will have a more family-like living environment, specialised therapy rooms and rooms built for family reintegration work. Melrose Care, the home’s sister agency, which provides subsidised counselling and specialised therapies for children and their families, will also be there.

About S$5.5 million of the S$22 million needed to rebuild the home has been raised so far, and the charity is looking for partners, said Goh.

Meantime, there has been good news for the participants in its Independent Living Programme’s housing component: After viewing more than 50 units, they found a place to rent and were given the keys last weekend.

James also recently enlisted for National Service and plans to return to polytechnic after that to complete his diploma.

For Ng-Tay and her colleagues, the dream is to have Melrose’s youths be contributors to society. “Imagine they’re living in a community where there’s a mix of rental and purchased flats, for example, and our kids form a network of resources for other families, (to meet) whatever needs,” she said.

“They shouldn’t be seen as just deficits to the community. So how do we do this piece of work such that they become enablers themselves, not just recipients of services?”