‘Not just about receiving a salary’: Why some adults in China have become ‘full-time’ children

One in five youths in Chinese cities is unemployed, and the situation could worsen before it improves. The programme Money Mind finds out why some young people cannot find jobs, and the unconventional choices some have made.

Money Mind talks to three Chinese youths about the realities of the job market: (from left) vlogger Zhang Jiayi, Beijing resident Qiu Qiu and social enterprise co-founder Will Wang.

HANGZHOU: Since the start of the year, vlogger Zhang Jiayi’s typical working day has looked like this: Talking morning walks with her parents, accompanying them to the market for groceries, preparing lunch, then taking a nap before tending to other chores.

The 31-year-old is a “full-time daughter”, a concept — and social media hashtag — that has surfaced as China’s youth unemployment in cities hits record levels.

Her parents pay her 8,000 yuan (S$1,500) a month. It is 20 per cent less than what graduates in her city of Hangzhou can expect, said Zhang, who used to sell clothes until the business succumbed to the pandemic.

The work of a full-time child, however, “isn’t just about receiving a salary or any form of compensation from parents”, she added. “It’s about genuinely enjoying the process of being with your parents and wanting to be there for them.”

That said, her salary from them is “well deserved”, she told the programme Money Mind in its special on youth unemployment in China.

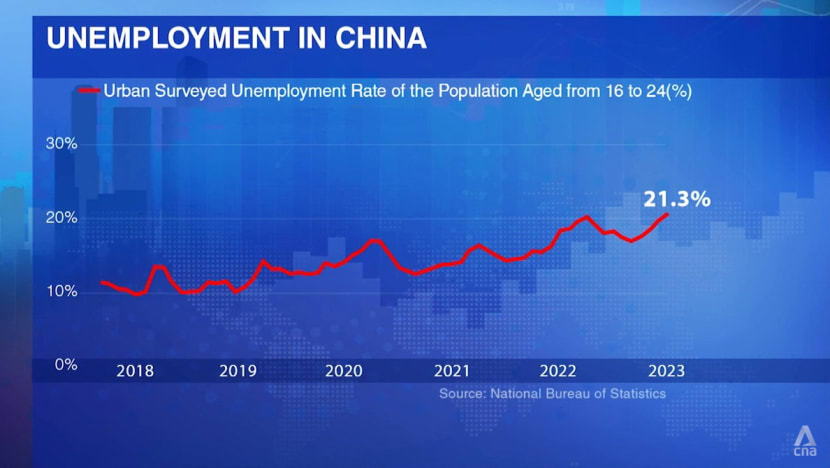

Unemployment among 16- to 24-year-olds in China’s urban areas rose to 21.3 per cent in June, compared with 4.1 per cent among those aged 25 to 59, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

As a new cohort of 11.6 million graduates join the workforce this summer, the figure could rise further.

China’s shaky economic recovery after lengthy pandemic lockdowns is partly to blame for the plight of its youth, although there are other reasons too, experts said.

Tertiary education enrolment increased from 30 per cent in 2012 to nearly 60 per cent last year, official figures show.

“They’re being educated and brought up for high-end jobs — tech jobs or jobs that require higher education,” said Nancy Qian, the James J O’Connor Professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences at Northwestern University in the United States.

The economic slowdown means those jobs are “shorter and shorter in supply”.

Zhu Hong, a professor of marketing and e-commerce at Nanjing University’s business school, said: “Our industrial structure hasn’t yet completed the shift from labour-intensive and low-end to high value-added technology or high-level service industries.”

As a result, “many graduates”, including master’s degree holders, are working as ride-hailing drivers and food delivery workers, she cited.

Zhu has even come across graduates from prestigious schools like Tsinghua University applying for sanitation jobs that “typically require only a high school or junior high school education”.

Another reason for the unemployment level is the tighter regulations, since 2021, on several sectors that are major employers of youths, said Bernard Aw, chief economist for Asia Pacific at credit insurer Coface.

These include the real estate, financial and private education sectors, and the tightening has meant a decline in jobs available to youths, he said.

WATCH: China’s unemployed youth — Why there aren’t jobs for new graduates (22:42)

The current situation prompted Chinese President Xi Jinping to exhort youths to be willing to “eat bitterness”, as quoted in the official People’s Daily newspaper on Youth Day in May.

Money Mind found out how three Chinese youths are navigating the realities of the job market.

FULL-TIME CHILD: ‘UNFAMILIAR TERRITORY’ AT FIRST

As with any other job, there has been a learning curve for Zhang in being a full-time child. In the beginning, she said, tasks such as cooking, driving and grocery shopping were “completely unfamiliar territory”.

“I couldn’t even distinguish between different types of vegetables at home,” she shared. But now that she has got the hang of it, “these tasks aren’t as difficult as I’d imagined”, she said.

Not all full-time children take up the role because of unemployment, said Zhu.

Some of them return home to take a break from big cities “where salaries are low, work is exhausting, (their) health is deteriorating, commutes are long and there’s no visible future”.

Others do it because they have some financial buffer as well as high expectations for a job.

Some youths from cities have grandparents who own valuable real estate — courtesy of privatisation reforms in the 1990s — that could be worth “a small fortune, like half a million dollars (or) a million dollars in the city centre”, said Qian.

“Knowing you have that … also reduces the pressure to take jobs that you find personally not ideal.”

Young people nowadays want a “reasonable income” but do not want to work overtime or their workload to be too heavy, said Li Zhuofei, a graduate of the Gengdan Institute of Beijing University of Technology.

But “most companies”, including state-owned enterprises, private and foreign firms, require overtime work, often without providing overtime pay, he said.

Experts say there are risks should youths remain full-time children for more than a few years.

“After a long period of isolation from the workplace and society, when the economy improves and they have the opportunity to re-enter the workforce, would they have lost the motivation … owing to the mentality of ‘lying flat’?” Zhu said.

WATCH: Meet China’s ‘full-time children’ — Why unemployed youths are working for their parents (10:06)

She was referring to the “bai lan” phenomenon: Disillusioned youths getting out of China’s rat race and doing the bare minimum to get by. Its equivalent documented in other societies is “quiet quitting”.

For now, Zhang’s family is “very supportive” of her decision, she said. “Even if I earn less money, they believe that what I gain emotionally is more important.”

RURAL OPPORTUNITIES?

In rural Xiangxi, Hunan province, Will Wang has found meaningful work in poverty alleviation and rural revitalisation for nearly six years.

Wang, who is from Shanghai, earned a master’s in international relations at New York University in the US. His social enterprise, Beyond the City, bridges the rural-urban divide by organising field study trips for both urban students and rural youths.

On trips to rural areas, urbanites live with local households and learn about ecology, traditional crafts and other topics from them. Rural youths, on the other hand, learn about the opportunities and challenges of urban migration on trips to cities.

While rural-urban migration slowed in China in the years before COVID-19, it declined in 2020 for the first time. That year, 10.1 million people returned to the countryside, 1.6 million more than in 2019.

More youths are willing to consider rural living because the government has improved infrastructure in the countryside — there is a 5G network in Xiangxi — and some do not want a fast-paced city lifestyle, said Wang.

The cost of living is also lower in the countryside, while the income “can be comparable”, he added.

Zhu, however, believes the younger generation would consider moving to the countryside only under certain circumstances.

“If the cost of living in the city is high and they can’t find jobs, in such a situation, instead of ‘lying flat’ or ‘bai lan’ or relying on their parents … it could be considered,” she said.

More of them would still prefer city living, she reckoned. “It aligns with their desire for social interaction, freedom and (vibrancy).”

PERFORMING ARTS DREAM, DATA ANALYSIS JOB

As for Beijing resident Qiu Qiu, she dreamed of working in the performing arts after graduating this year with a master’s in literature of theatre, film and television.

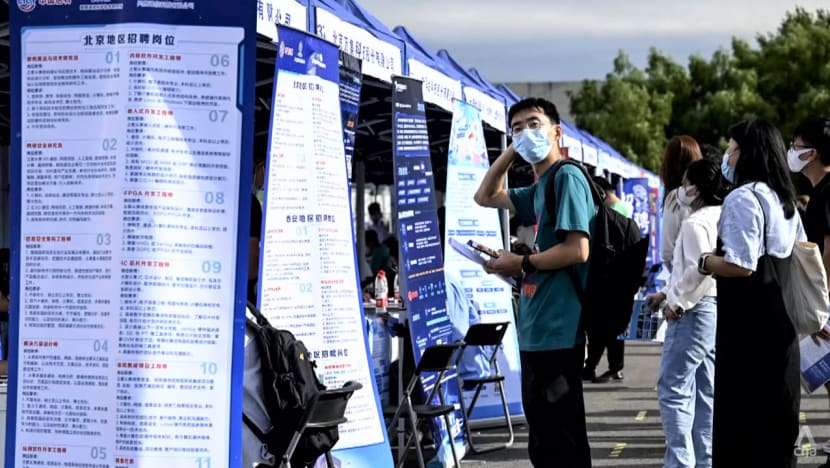

She sent dozens of job applications to television stations and media companies, even internet giants. But there was nary a response. Most of her resumes “seemed to sink into the abyss”, she described.

Qiu cast her net wider and managed to clinch a data analysis role in the human resources industry last month. It pays 14,000 yuan a month but “deviates quite a bit” from her field of study, she acknowledged.

It is important, however, to try different opportunities and be open to career advice dished out during the interview process, she said. “The key is to take the first step and engage with various job opportunities in society.”

Experts say there are gaps to bridge, for example between the jobs available and what youths aspire to and between youths’ salary expectations and what companies are willing to offer.

There are job openings waiting to be filled, such as technical and front-line positions in manufacturing, said Nina Wu, a human resources supervisor. These may not be the jobs, however, that “educated elite youth want”, noted Qian.

The typical salary for entry-level factory positions is around 2,000 to 4,000 yuan a month but could go up to 7,000 to 8,000 yuan in cities like Shenzhen, said Wu.

Some advanced degree holders may have to look at similar salaries. Qian knows a graduate from one of China’s top five law schools who is looking for work in Shanghai, one of the country’s costliest cities, but faces monthly wages of between 3,000 and 7,000 yuan.

Schools may need to develop programmes and train their students for “priority sectors” such as advanced manufacturing, semiconductors, electric vehicles and new energy sources, said Aw.

Although the Chinese economy is still recovering from COVID-19 measures, and youth unemployment could moderate in the coming years, it will remain at higher levels than a decade ago, reckoned Qian.

“We should be looking at that as a generational problem,” she said.

Watch this Money Mind special here. New episodes every Saturday at 10.30pm.