Paradise island Lombok, its poisoned gold, and the children who suffer

Informal gold miners in Indonesia rely on mercury to extract gold from ore. But at what cost? The programme Undercover Asia finds out how their families are being poisoned, enabled by an illegal trade and corruption.

Faturahman is one of Indonesia’s many informal miners who use mercury in gold processing.

LOMBOK, Indonesia: It is a diver’s paradise. Famed for its golden beaches. A draw for millions of tourists, including Singaporeans, over the years.

But the island of Lombok has a hidden treasure. And a dark secret.

In its volcanic hills lies gold. That is why Lombok has one of the densest populations of gold miners in Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s biggest gold producer. They work in a poorly regulated, multi-billion-dollar industry fuelled by a deadly element: mercury.

The miners rely on the toxic metal — and its illegal trade — to extract gold from ore. But they are being poisoned slowly. Exposure to mercury can cause irreversible harm, even death.

And the toxin is spreading. To their families, neighbours, communities in Lombok and beyond.

The danger begins when the miners return home from the mountainsides to process the rocks they excavate.

The rocks are placed in a ball mill, a horizontal cylinder that uses ball weights for grinding as it is rotated. Water is also used to break down the rocks into sediment. And mercury is poured into the ball mill to bind with the gold.

The mercury is then burned away, leaving behind pure gold — and poisonous fumes. The toxic waste water is discarded into the environment.

Gold miner Faturahman, who, like many Indonesians, goes by one name, has learnt of the dangers of mercury to humans. “But there’s nothing I can do,” he said. “I don’t know how to process the rocks without using mercury.”

His work has come at a great cost. A day after his son’s birth, Faturahman realised that the baby “didn’t want to suckle” and kept vomiting. “I called the doctor right away to ask for help,” he recounted.

“The doctor took a biopsy to investigate the issue. The problem was in his intestines. They weren’t functioning properly.”

Owing to his deformed intestines, the child is unable to move his bowels. Instead, the excrement must be sucked out daily through a tube.

“The doctor taught me how to treat him,” said Faturahman. “Only I and my wife can carry out the procedure.”

The couple are not alone, however, in worrying about their child. When the programme Undercover Asia visited local doctor Teguh, he was examining four children whose conditions worried him because of a possible common thread.

One of them was constantly drooling, which had started after the child had seizures.

Another who had started having seizures was also deaf. The child’s mother said she had been exposed to mercury even before her daughter’s birth. Her husband is a gold miner.

“There are indeed patients who have symptoms suggesting poisoning,” said Teguh. “I’m very concerned because I also have a young child.”

His clinic is in Sekotong, a West Lombok district consisting of three villages, where most of the population are reliant on gold mining.

Non-governmental organisations working in and around the area have counted nearly 50 children born with neurological and physical birth defects since 2018.

UNDER-THE-RADAR ILLNESS

Mercury poisoning was once tied to power generation and manufacturing, used in light bulbs, thermometers, cosmetics and more. But by the 21st century, most industries adopted alternative, mercury-free production methods.

Then, in Lombok, a new danger emerged. Informal gold mining started almost 15 years ago after a mining company found “large deposits” on the island, and locals spotted an opportunity, said environmental health specialist Yuyun Ismawati.

It has been estimated that 22,000 people in Lombok depend on small-scale gold mining — done on land they do not own — to earn a living. But until now, the small-scale mining activities have been illegal, Yuyun added.

Lombok’s miners are normally secretive about their work, but Faturahman agreed to share his story. Born on the island, he used to be a fisherman, “but it was so hard to get a good income”. So he became a miner.

Just half a gramme of gold is worth 300,000 rupiah (S$26) to him, which is more than twice the amount he earned daily as a fisherman.

Globally, around 20 per cent of gold production comes from informal miners like him. But their use of mercury complicates matters. And illness in Lombok’s mining communities has largely flown under the radar of medical authorities.

WATCH: The real price of Indonesia’s mercury-poisoned gold (46:18)

NGO efforts to collect samples from Lombok’s residents have also not been extensive, which is why medical researcher Adriana Ekawati at Mataram University, located on the island, is leading a team to conduct biomarker testing in the community.

“We’re motivated by the fact that this is our problem,” she said. “We have to be more curious about how big the problem is.”

First on her list was Faturahman and his family. The initial findings from cognitive tests indicated that he already has health issues.

“The co-ordination between the left and right movements is unbalanced,” said Adriana. “His ability to co-ordinate fine motor skills is also slower than the average person.”

Hair samples were also taken, and his test results showed a mercury concentration that was 12.7 times higher than the safe threshold of one part per million. The reading for his baby boy, Nazil, was four times the safe level.

Out of 10 individuals initially tested in Sekotong, none were safe. The sample of one gold miner was analysed to be 26.7 times higher than the safe level. For another individual, a former miner, it was 9.8 times higher. And for his child, 5.3 times.

“We should be very concerned,” said Medicuss Foundation co-founder Jossep Frederick William.

The first clinical signs, such as co-ordination being affected, usually manifest within five years, he said. The second phase is often severer: Patients can present with organ failure or neurological decline. And children are more likely to be impacted severely.

“The severity depends on how much mercury is in the body and the person’s resistance to mercury, which varies highly,” said Jossep.

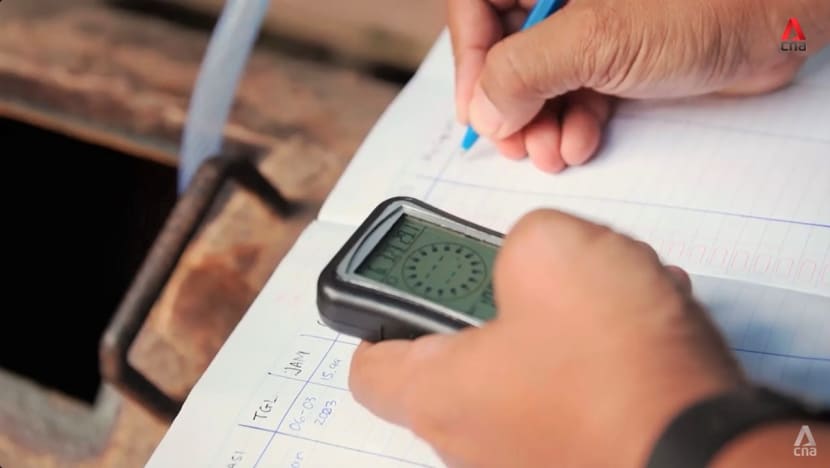

Investigations at Faturahman’s home included measurements of mercury in the air, using a portable mercury analyser. A reading above 1,000 is considered unsafe, while 8,000 to 10,000 is a level that calls for evacuation.

The mercury concentration around his ball mill was 8,657 nanograms per cubic metre.

But that is not all. Burnt mercury that has turned into vapour will accumulate in the air until one day, somewhere, it falls as toxic rain. “It’ll move wherever the wind takes it, so it’s impossible to avoid,” said Jossep.

Contaminated waste water from miners’ ball mills also finds its way into drinking wells, paddy fields and the rivers and seas where people fish.

“Research conducted … such as (by) Mataram University shows that in the vegetables and fruits and other food production (in Lombok), mercury is present,” said Jossep.

Mercury does not break down in the environment. The more it is used, the more it builds up in the food chain.

ILLICIT BUT THRIVING MERCURY TRADE

As informal miners in many countries also use mercury to extract gold, the environmental health issues in Lombok are not unique. But Indonesia is the world’s second-largest source of mercury emissions (after China) from artisanal and small-scale gold mining.

There are an estimated 850 small-scale mining hot spots across the Southeast Asian nation and at least 300,000 small-scale gold miners. Estimates of how much mercury they use varies widely, from 300 tonnes to more than 3,500 tonnes annually.

Mercury is made from an ore called cinnabar. Mining and refining of the ore are not unlawful under Indonesian law if done with a permit, but the government has said it has not issued any permits.

Yet, an illicit domestic production and supply chain for mercury is thriving.

One of Indonesia’s largest cinnabar hot spots is on Seram island, Maluku. Attempts to shut down its mines were publicised in 2017 and 2020. But satellite pictures taken last August showed mining activity, with blue tents hiding the excavation work and machinery.

Local journalists such as Rislan are trying to expose these mining camps. What he recently saw, up on the mountainside, confirmed the images. He also talked to men who were washing and crushing the ore, in preparation for its refining.

“There were lots of tents set up on the cliffs, so there was no way the activity would go unnoticed,” he said. “This raises the question whether certain parties are co-ordinating or turning a blind eye.”

Dyah Paramita, a researcher at the Centre for Regulation, Policy and Governance, pinpointed law enforcement as one of the problems.

“Weak law enforcement is caused by several factors, for example the involvement of law enforcement officers or inadequate capacity of human resources in the field,” she said.

“Based on the database I’ve compiled, there appears to be a trend of involvement by local officials.”

In one case in Sukabumi city, West Java, court documents showed that cinnabar was delivered using an Indonesian National Armed Forces truck, she cited. “I also received a court decision in Ambon, where the police were involved in trading mercury.”

In recent years, illegal refineries have been spotted in Maluku province’s Ambon, West Java’s Bogor city and East Java’s Jombang regency. But they are constantly on the move to evade detection.

Hence, Indonesian gold miners have a plentiful supply of mercury, despite a ban on its use in small-scale gold mining.

Traditionally sold through middlemen, it is even available on social media platforms such as Facebook, with sellers providing the delivery. Facebook’s parent company, Meta, did not reply to Undercover Asia’s queries about why this is happening.

PLAN OF ACTION SET OUT

The government has committed internationally to dealing with the mercury problem.

In 2017, it ratified the Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global treaty designed to protect human health and the environment from the dangers of mercury. Today, 100 countries have ratified the convention.

According to Indonesia’s subsequent National Action Plan, the target is to eliminate mercury use in small-scale gold mining by the end of 2025.

This starts with prohibiting cinnabar mining, and to this end the plan proposes that a draft regulation be issued. The recommendations include the “prevention of the existence of cinnabar smelters” and prevention of the “free trade of mercury online”.

Tougher enforcement of laws was also recommended, as was the adoption of alternative technologies for gold processing.

Experts are already trying their best to persuade miners to change their ways, for example through education programmes in the field. “Ultimately, they were of the opinion that it’s their risk to take,” said Jossep.

“Mercury has its disadvantages. But it also has advantages,” said gold miner Sukriya. “If we don’t use mercury, we won’t get the gold.

“When it comes to (gold) mining, it’s important because there’s no other work. You can only do mining here in Sekotong.”

NGOs have not given up. In Lombok, they have introduced a new method of gold extraction: Mills that make use of cyanide. Although cyanide is also poisonous, there is less danger of residual build-up in the environment compared to mercury.

Miners may also need to use up to 20 parts mercury for one part of gold recovered, whereas cyanide yields more gold. “That’s what got them interested in using the cyanidation process,” said Hamdani, who heads the Tibu Batu Co-operative.

The co-operative built a processing plant for miners, but it has proven tricky in execution. “Extracting gold using mercury is a quick process; it only takes two to three hours,” said Hamdani. “But the cyanidation process can take 72 hours.”

That is not the only hurdle. Each day, miners such as Faturahman usually haul two sacks of ore at most. But cyanide processing requires a huge amount of ore in one go, ideally 150 sacks.

Even if miners could afford to wait, the extraction cost is too high individually. As members of a co-operative, however, they could potentially deal with the issues of cash flow and time.

But the most important hurdle is that “the way we process gold is somewhat illegal”, cited Hamdani. “Up until this point, we’ve not obtained permission from the government. We’re still in the process of obtaining the permit.”

The possible solutions, and the regulations needed, are apparent to Jossep.

“First, (the miners) can’t destroy nature. Second, they have to use cleaner methods without mercury. Third, a system is set up so that the gold they produce can be officially purchased by the state,” he said.

“This would provide a huge amount of foreign exchange for the country.”

The potential rewards for upskilling and harnessing the products of Indonesia’s informal gold miners could be huge, if the authorities can overcome the obstacles and if there is help from stronger international regulations.

“One shortcoming of the Minamata Convention in respect of small-scale mining is that the treaty regards this mining as an allowed use for mercury,” said Marcos A Orellana, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights.

The position should be the other way around — that mercury should be banned.”

If black markets are not shut down, however, gold miners will continue to use mercury. It is the youngest generation, and succeeding generations, who will ultimately pay the heaviest price.

For Faturahman, his child’s illness has left him in the unenviable position of having to mine more gold to pay for surgery. “Because I don’t have insurance, it’d cost around 30 million rupiah. I don’t have that kind of money,” he said.

“Though this is the state we’re in, I’ll do my best to keep my son healthy. I know that he isn’t like a normal child, but I’m still grateful for his birth. I hope my son will be healthy soon.”

Watch this episode of Undercover Asia here.

Read this story in Bahasa Indonesia here.