A lab for bespoke drug treatments — where AI, researchers find ways to help cancer patients

There was little hope when a 24-year-old had to fight a rare, terminal cancer. A clinical study and digital medicine platform at National University of Singapore’s Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine helped fend off the disease for 16 months.

In partnership with the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

Donavan Koh put up a good fight against a very deadly disease, said his doctor.

SINGAPORE: He had just completed the “great experience” of full-time National Service and was looking forward to the future after having studied gaming at the Institute of Technical Education.

Four months later, in January 2020, Donavan Koh’s voice began to grow hoarse.

What he initially thought was a sore throat worsened to the point where his parents could not hear what he was saying. His father had a hunch that it was abnormal and got him to see a doctor.

The result of the biopsy shocked Koh: It was Stage 4 natural killer (NK) cell lymphoma, a “very rare” variant of lymphoma, diagnosed his doctor, Daryl Tan, a haematologist in private practice.

Lymphoma is a cancer that starts in infection-fighting white blood cells called lymphocytes, which are part of the body’s immune system, according to the National University Cancer Institute, Singapore (NCIS).

On his doctor’s advice, Koh immediately started chemotherapy, the first-line treatment for his condition.

The side effect made him cry. “After two months, my hair started to fall,” said Koh, who had not told his friends about his condition. “I was devastated because I care a lot about my appearance.”

Worse still, the treatment did not work.

It was time to put him on standard second-line drugs. Only about 40 per cent of patients, however, respond to this treatment. Koh was not one of them, and his situation was dire at this point.

“There isn’t any proven way to treat the disease after a patient’s relapsed or progressed beyond the first one or two lines of treatment,” Tan said.

For many patients, the next step is palliative care, which focuses on relieving the suffering and improving the quality of life of people with life-threatening illnesses.

But Koh, 24, was “probably the youngest” patient with the disease Tan had ever seen. NK cell lymphoma typically affects people aged 55 and over, and Tan estimates that there are about 20 new cases yearly in Singapore.

Koh’s parents were distraught. To try to “salvage” the situation, Tan called a doctor-researcher conducting a clinical study in the National University of Singapore (NUS) Centre for Cancer Research (N2CR), a translational research programme at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine), to ask if it was open for enrolment.

The study, involving a digital medicine platform called Quadratic Phenotypic Optimisation Platform (QPOP), let Koh live cancer-free for 16 months.

FINDING THE BEST DRUG COMBINATIONS

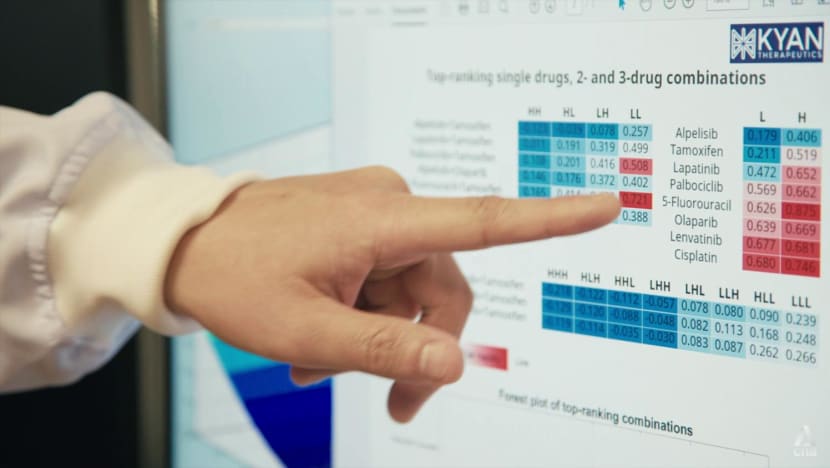

First, doctors took a sample of his cancerous tissue, which was then incubated with 155 drug combinations for up to 72 hours.

From a set of 12 drugs chosen by the researchers, QPOP had generated over half a million drug combinations that were possible for Koh, then ranked the different drug cocktails and identified the most effective one for him.

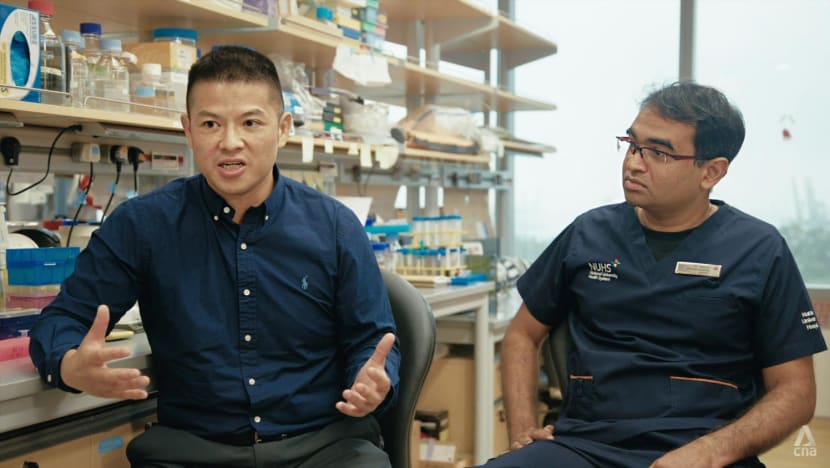

Driven by robots and artificial intelligence, QPOP accomplished the task in the span of about six days — which would be impossible with manual tests, said Edward Chow, an associate professor at the N2CR and principal investigator at the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore (CSI Singapore), NUS.

His team started working on QPOP in 2012 and have applied it to medical settings since around 2017. A collaboration among molecular biologists, cancer researchers and engineers, QPOP “marries the wet lab with computer science and mathematical analysis”, said Chow.

Simply put, the platform is “a bartender lab for cocktails of drugs”, said fellow N2CR assistant professor and CSI Singapore principal investigator Anand Jeyasekharan.

“Edward’s lab (team) are like expert bartenders. They come up with the best cocktails of these anti-cancer drugs, which are … bespoke for our particular patients,” said Jeyasekharan, who is also a consultant in the department of haematology-oncology at the NCIS.

The individualised treatment offered through QPOP is a departure from cancer treatments where doctors follow standard protocols.

In the first round of routine treatment, patients would be prescribed a combination of drugs that “typically has a chance of working” for people with a particular type of cancer.

It is akin to every customer at a bar getting the same drink “whether or not they like it”, Chow said.

Not everyone will have a good response to the drugs — certainly not Koh in his first two lines of treatment. When this happens, doctors often feel helpless, said Jeyasekharan.You wish there’s something else that you could do.”

He added: “There are plenty of new drugs being discovered every day, but we’re often still uncertain as to how best to use these new drugs, which patients should be receiving a particular new drug over another, (and) in what combination.”

These are the “unknowns” that Chow’s team and QPOP seek to solve.

WATCH: Personalised cancer treatment (6:51)

MORE OPTIONS, TIME FOR PATIENTS, FAMILIES

Chow’s motivation for doing cancer research is personal: When he was in graduate school, his father was diagnosed with renal cancer.

Chow witnessed the progression of the disease as his father went through “the different lines of standard therapy until, ultimately, he ran out of options”.

“We did feel helpless, especially because his treatment was very regimented, so I wanted to see if I could do anything to make sure that people have as many options as possible,” he said.

He decided to switch his area of research — which was on the effects of antiviral immune response on drug metabolism — to cancer, for more clinical impact and “to give cancer patients and their families as much time together as possible”.

And that was what he did for Koh.

QPOP ranked two drugs highly for the patient, but both were not approved for use in Singapore at the time. The medical team successfully sought to bring the drugs here with the Health Sciences Authority’s approval.

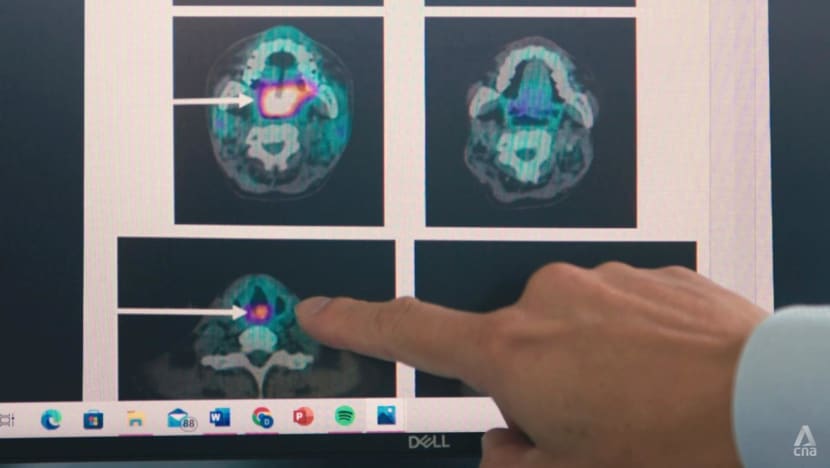

To the doctors’ surprise, Koh, who had been unable to talk intelligibly for about six months, regained his voice after the first treatment cycle, said Tan.

“He couldn’t talk because the tumour was in his voice box,” the haematologist said. “But when he started to vocalise more clearly and began speaking in proper sentences, his parents were extremely overjoyed.

“When we did the scan after two cycles of treatment, we were pleasantly surprised (to find) that … the tumour in the body had all cleared.”

The first QPOP drug cocktail staved off Koh’s disease for 10 months. When it returned, he was given another set of highly ranked drugs, which helped him beat the cancer a second time.

But in June, he had a “very aggressive relapse”, said Tan. As the treatments and disease had left him very frail, doctors could not treat him further, and Koh succumbed to cancer on July 12.

“He put up a good fight against a very deadly disease,” said Tan.

He defied the odds, lived a very meaningful one and a half years, spent good time with his family. And most importantly, he’s paved the way for better treatments for patients with this condition.”

STILL WISHING TO DO MORE, AND BETTER

The scientists will keep working to make individualised treatment a reality for more patients. “There’s still more to be done. We still need to figure out how to keep (cancer) away once it’s gone away,” said Jeyasekharan.

The researchers believe QPOP can ultimately apply to all types of cancer, but this will depend on advances in culturing cancer cells and tumour tissues in the laboratory, Chow said.

He and Jeyasekharan want to find a way to incorporate more drugs into QPOP’s drug set — not only drugs that work directly on cancer cells, but also those that help patients’ immune cells to target and attack cancer cells.

And “maybe in future”, instead of harnessing a platform like QPOP only after standard treatments have failed, scientists and doctors will be able to conduct tests earlier to see if there are “less toxic” options available for patients, said Jeyasekharan.

This would spare some patients the side effects of standard treatments — and reduce costs by giving patients drugs that are more likely to work for them.

“Cancer costs are the number one healthcare expenditure, so we need to find ways to rationalise the use of these expensive drugs,” he said.

Thanking the Kohs for putting their trust in the study, Chow said they have helped the medical team “learn more about (ways) to improve the platform and the technology, so that we can hopefully benefit more people in future”.

On what he would tell Koh, Jeyasekharan said: “I wish science worked faster, Donavan … I wish we could do more and better. That’s something we’ll continue to work towards.”