Buy a S$10 power bank or pay more? Your safety may depend on it, among other things

Cost may be a factor when buying a power bank. But does price correlate with how safe these portable chargers are? The programme Talking Point has some of them stress-tested, with varying results.

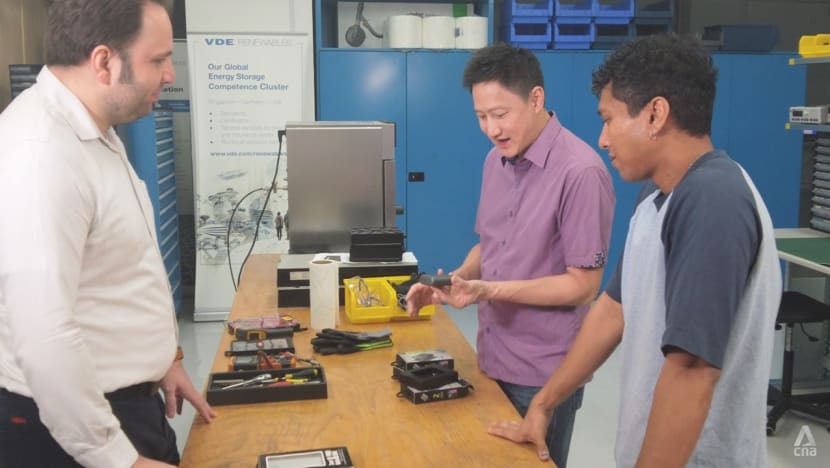

Talking Point host Steven Chia inspects a charred power bank.

SINGAPORE: Earlier this year, a fire erupted on board a Scoot plane shortly before it was supposed to take off, caused by an overheated power bank. Two passengers were injured.

A few months on, in a Talking Point poll of nearly 800 people on Instagram, a third of them still thought they are allowed to use their portable charger on a plane that is taxiing before take-off or after landing.

This is a false belief. Passengers are allowed to use power banks only when a plane is cruising at altitude.

Explaining why, Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore’s head of dangerous goods, Vincent Koh, said: “At cruising altitude, the cabin crew is able to move around in the cabin.

“In the event of an incident involving a power bank, the cabin crew … can attend to (it) very quickly.”

In the last eight years, out of nine incidents involving lithium-ion batteries that were carried aboard aircraft operated by Singaporean operators, five involved power banks, he disclosed.

Power banks pose a danger not only on planes, however. In Singapore, 38 fires caused by power banks were recorded between 2018 and last year — joining a long list of incidents from round the world caused by these portable battery chargers.

The devices can come in an array of options, whether bought off the shelf from local retailers, at street bazaars or online.

Prices can range from as cheap as S$10 for a non-brand power bank with a 20,000 milliampere-hours (mAh) capacity to S$50 for a branded one with a smaller power capacity.

When it comes to safety, the question is whether there is a difference between the various types of power banks. And what could be next in a world increasingly powered by rechargeable batteries?

THE SAFETY REQUIREMENTS

Portable power banks fall under the Consumer Protection (Consumer Goods Safety Requirements) Regulations. This means suppliers in Singapore are to ensure that the relevant safety standards are met before the power banks are sold locally, including online.

While pre-market testing, certification or approval from the Consumer Product Safety Office is not a requirement, the office does post-market checks on the adherence to safety standards.

Vendors who continue selling power banks after being directed to stop their sale, or who are directed to inform users of the potential dangers of the devices but fail to do so, may face a fine and/or imprisonment.

WATCH: When power banks explode — How safe is your portable charger? (22:36)

“When you just buy online from overseas — you go to Taobao or something similar — you don’t have this kind of protection because it’s outside the Singapore government’s purview,” said Andreas Hauser, head of energy storage systems at VDE Renewables Asia.

“(Power banks) aren’t forbidden (from being) imported. But you may get something that … may be quite dangerous.”

In Singapore, lithium-ion batteries in portable power banks must comply with the safety standard numbered 62133-2 by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). And in shops, Hauser has seen this certification indicated on power bank boxes.

But the safety expert warned: “The manufacturer may not necessarily include it. … It’s not required that there be some kind of sticker on the device.”

For example, two sets of power banks bought from an online marketplace and a gift website — costing S$10 to S$15 each — did not have this label, whereas a set of branded power banks that Talking Point bought off the shelf, at S$50 each, did.

A BATTERY OF TESTS

To ensure the safety of power banks, several tests must be done — which Hauser demonstrated to find out the differences among the purchased devices.

In a case stress test, they were put in an oven at 70 degrees Celsius to see if any casing “opens up and deforms”, which would expose its internal components. All of them passed this test and were still working.

The power banks also passed the short-circuit test. “The protection electronics were good enough,” said Hauser, who has spent 18 years testing batteries.

The other tests, however, yielded different results.

As overcharging is one of the main causes of fires, in the third test, more voltage was applied to the power banks than they were normally able to take. Two devices died, as they were supposed to, said Hauser.

“They passed, (because) from a safety perspective, (there should be) no fire, no explosion.”

But in the third power bank — which was unbranded, with certification unknown — the battery bloated up and bent the aluminium casing. Yet, the device was working, which made it dangerous, said Hauser.

“The normal user (might think) it’s fine to use. But it’s not,” he warned. “Eventually it’ll pop.”

Even so, it passed the overcharging test because it did not catch fire. “It’s not a fail. But it’s definitely a cause for concern,” he said.

In the next test, the power banks were vibrated with “relatively high” frequency. When one of the cheaply made devices with unknown certification status was opened later, he saw the battery cells held in place by a strip of glue.

Should the glue fail, which he thought would be probable, the cells would not be securely in place.

“These cells are the heaviest part of the power bank, (which) means that when you walk, when you’re on the bus (or) in a car … this is rattling around. And all this moving causes stress on the cable,” he said.

“Eventually, this may rip. … If you’re unlucky, then this cable (comes into) contact with another point, and then you get a short circuit. And then the short circuit leads to overheating, to fire.”

Still, the power bank passed the vibration test because the duration of the test had been truncated. “If we do the full 12 hours, it’d probably fail,” reckoned Hauser.

By comparison, the branded, certified power bank had no cable and used a metal strip instead — welded on so that it will not “come off so easily”, with the battery cells fitting snugly in the case, he observed.

The last test was the drop test: The power banks were dropped onto a steel floor from a height of one metre. All three samples did not break open, but the aluminium one “popped open a little”, observed Hauser.

If you then put it in your pocket again, where (a) key is inside, or something, then you’ll short it out.”

As the internal circuitry was exposed, the device was problematic, he said. It failed the test, while the other two power banks passed.

FLIGHT RULES

The risk of power banks catching fire is the reason for the rules on their use on flights. And most of Talking Point’s poll respondents knew there were restrictions on the type of portable chargers allowed in their hand luggage.

For example, passengers should not carry power banks exceeding 27,000mAh. “When the capacity of the power banks gets bigger, … the risk and the effects of power banks catching fire will be a lot greater,” said Koh, the dangerous goods expert.

Passengers are also required to protect their power banks by placing them individually in a plastic bag or protective pouch made of non-conductive material.

Among other restrictions cited by Koh, passengers should not place power banks with metal objects, such as coins, keys and safety pins, to avoid a short circuit. They should also not carry damaged power banks aboard a flight.

A third of respondents, however, falsely believed that they must put their portable chargers into their checked baggage.

“Power banks contain lithium batteries. And lithium batteries are inherently flammable in nature, … especially when the power banks are damaged or when they aren’t manufactured according to safety standards,” said Koh.

When they are carried into the aircraft cabin, then the crew can attend to any incident, he noted.

On the final poll question — whether it is okay to charge a portable charger by plugging it into the in-flight entertainment system — 59 per cent of respondents said no.

The answer is, “it depends”, said Koh. Power banks can be charged using the in-flight power supply only when the plane is cruising at altitude.

A POSSIBLE SOLUTION

On the ground, two scientists in Singapore are leading the charge towards safer lithium-based energy storage systems — by upcycling waste plastic bottles into polymer electrolytes for batteries.

“We take the plastic bottle and turn it into something more valuable than the actual plastic bottle,” said Jason Lim, deputy head of soft materials at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research’s Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE).

While electrolytes are typically in liquid form, as used in today’s lithium-ion batteries, the scientists have derived solid polymer electrolytes from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic.

Liquid electrolytes contain carbonates, which are “very flammable”. “Our electrolyte … (does) not contain any carbonates,” said IMRE deputy head of polymer composites Derrick Fam. “It doesn’t burn so easily.”

Typically, liquid electrolytes are also manufactured from “pretty expensive materials”, he added, whereas plastic bottles cost “very little”, so the scientists’ potential product “could cost a lot less”.

But he cautioned that bringing it to market “could take a while” because of the processes — “of optimisation, of the making of these electrolytes, to integrating them into batteries” — that must be done before commercialisation is possible.

He cannot say for sure if this will even happen within five years, only “not anytime soon”. Meantime, he warned about the dangers of leaving a power bank unattended — “and it’s overcharging”.

For those shopping for one, Talking Point host Steven Chia suggested “one with the necessary protection against overcharging and therefore overheating”.

From the results of the stress tests that were done, it seems to him that price reflects the quality, and thus safety, of a power bank.

“At the very least I should look for one that’s clearly labelled,” he said. “And if you can’t find (the safety standard label) on the box, you can always drop the manufacturer an email.”

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.