CNA Explains: What escalating Red Sea tensions mean for the world, including Singapore

An intensifying situation in one of the world's busiest trade lanes is stirring up the biggest upheaval to global commerce since the pandemic. CNA's Tang See Kit looks at how it began, the potential ripple effects and how it could end.

A Houthi military helicopter flies over the Galaxy Leader cargo ship in the Red Sea in this photo released Nov 20, 2023. (Photo: Houthi Military Media/Handout via Reuters)

This audio is AI-generated.

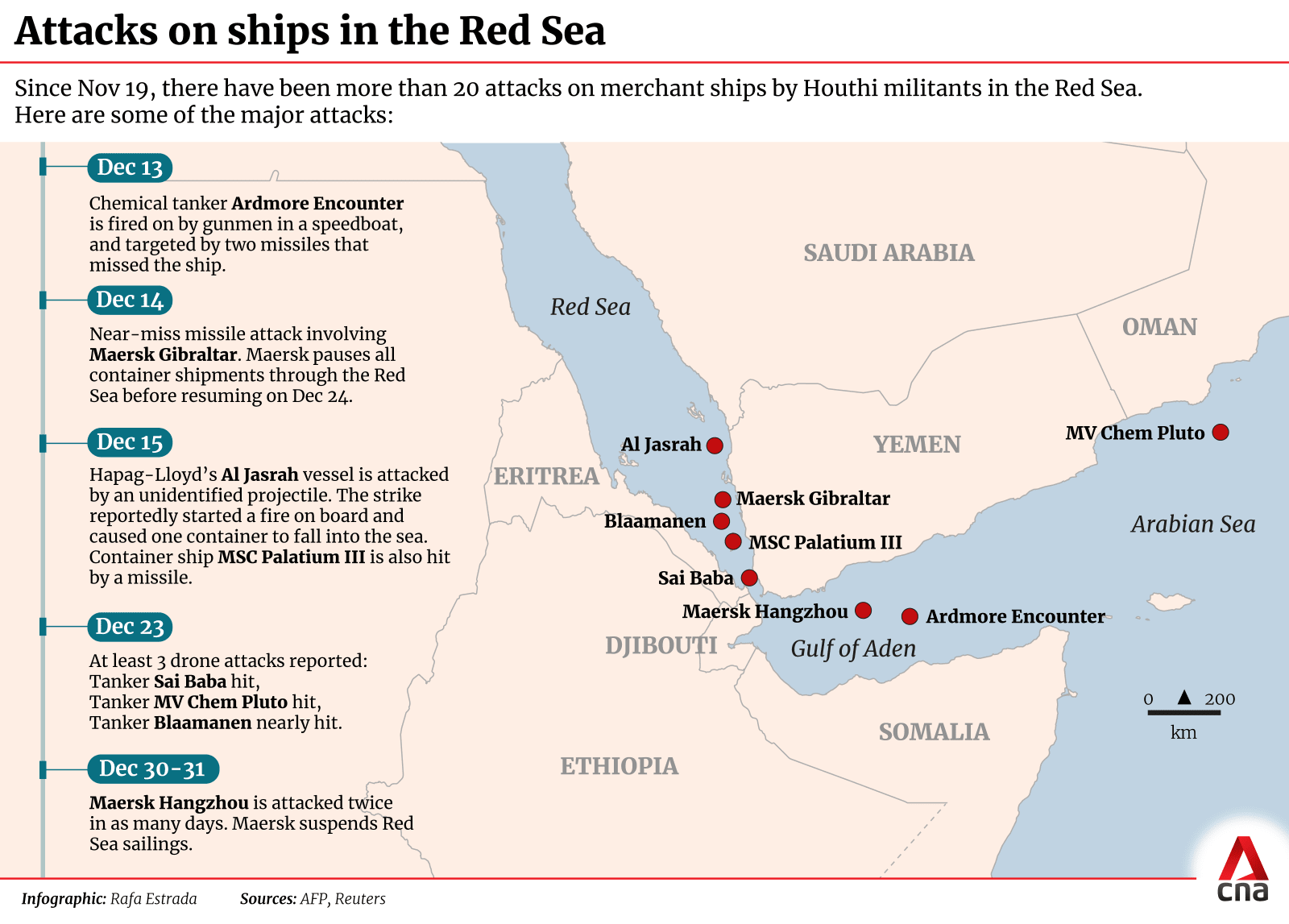

SINGAPORE: From drones and missiles to gunmen on speed boats, attacks on ships plying the Red Sea have escalated in recent weeks.

Singapore on Wednesday (Jan 3) joined 13 other countries in condemning these attacks carried out by the Houthi militants, warning of unspecified consequences if they continue.

This came shortly after members of the United Nations Security Council also called for a halt to the attacks in what is one of the world's busiest shipping lanes.

What’s happening in the Red Sea?

Since Nov 19, there have been more than 20 attacks on commercial vessels in the southern Red Sea and the Bab al-Mandab Strait off Yemen.

This is the work of the Houthis - a militant group that controls much of Yemen - who say they are responding to Israel's bombardment of Gaza by targeting ships linked to Israel or heading into Israeli ports.

However, ships with no direct connection to Israel have also been affected.

In response, a United States-led multinational naval force – dubbed Operation Prosperity Guardian – has been set up to secure the vital seaway and intercept Houthi strikes.

US warships shot down two missiles and sunk three out of four Houthi boats that were targeting a Singapore-flagged container ship operated by Danish shipping giant Maersk.

Following the clash over the weekend, Iran dispatched a warship into the Red Sea. The US has accused Iran of being “deeply involved” in the Houthi attacks, which Tehran denies but says it understands the reason for the militia's actions.

The situation has prompted some of the world's largest container-shipping firms, including Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd and Mediterranean Shipping Company, to stop sailing through the area and take a detour instead.

Why is the Red Sea so important?

The Red Sea, which is bookended by the Suez Canal to the north and the Bab al-Mandab Strait to the south, is a busy waterway offering access to the shortest shipping route between Europe and Asia.

Around 12 per cent of global trade passes through the Red Sea, including as much as 30 per cent of container traffic and over US$1 trillion worth of goods a year.

The Suez route was in turn disrupted in 2021 when a 220,000-tonne container ship ran aground for almost a week, blocking the canal in both directions and resulting in a backlog of more than 400 ships delayed.

With the key global trade artery again in flux, shipping liners have resorted to rerouting shipments around Africa’s southern Cape of Good Hope.

This adds at least 10 days to the duration of the trip and more than 15 per cent to shipping costs, said S&P Global Market Intelligence’s head of supply chain research Chris Rogers.

Control Risks’ director Cormac Mc Garry said a large ship may incur about US$100,000 in fuel cost for each day of travel.

And this excludes extra costs for insurance, wages and fees to call on other ports along the way, said Associate Professor Goh Puay Guan from the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School.

What's the immediate impact?

Already, freight rates - or the cost charged by liners to move goods in a shipping container - between Europe and Asia have shot up by about 20 per cent to a range of US$1,800 to US$2,100, said Ms Sarah Mangeet Kaur, general manager of freight forwarder AOCL.

A “war risk” surcharge, ranging from US$500 to US$800, has also kicked in.

As the impact from the re-routing of ships deepens, these costs are expected to go up further in the coming months, said Ms Kaur.

Shipping lines have already shortened the validity of their quoted rates from three months to two weeks, adding to more uncertainty over costs, she noted.

Meanwhile, late shipments are a certainty, with AOCL seeing some of its cargo from Europe being delayed by almost three weeks.

It also has containers that have been waiting at ports for weeks to be picked up.

“My customers are now frantically trying to see whether they can get the delayed cargo by air freight instead, which was the alternative when we had the Suez Canal blockage previously,” said Ms Kaur, whose company deals with mainly chemicals and general cargo like marine equipment.

Consumers will also be hit, particularly those in Europe, said Mr Mc Garry.

Beyond containerised goods such as frozen food, toys and furniture, the Suez route provides a vital passage for energy shipments from the Middle East to Europe, as the region weans itself off Russian supplies.

Given the winter season, the delay to container ships carrying fossil fuels to Europe may be felt first, with the gas market likely to be hit with minor price increases, he added.

Data from S&P Global Market Intelligence showed that over 300 industrial categories and 6,000 products were shipped from Asia and the Gulf by sea.

This amounts to 14.8 per cent of all imports into Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

What happens if this drags on?

A key question in the longer run is whether the Red Sea troubles could spark a supply chain crisis and in turn, spillover effects on an already-slowing global economy.

And the Red Sea is not the only maritime trade route facing issues.

The Panama Canal – which carries 5 per cent of seaborne trade, particularly US fuels and grains bound for Asia – has been suffering from low water levels linked to drought. As a result, it is operating at only 55 per cent of its normal capacity, according to research firm Capital Economics.

Transits remain restricted for the coming months, although the canal authority has said it will increase the number of transit slots from mid-January.

“When you reroute, the kind of clockwork that global shipping goes through will be upset. There will be a lot of catching up to do … with the risk of a bullwhip effect,” said NUS’ Assoc Prof Goh.

The bullwhip effect is a supply chain phenomenon describing how small fluctuations can be amplified and cause bigger repercussions down the chain.

The diversions could, for example, see congestion at ports that are not supposed to handle large traffic.

Or there could be a shortage of vessel space as empty containers get stranded in the wrong places.

All these would compound delays and possibly even have a spillover impact on other shipping routes beyond those between Europe and Asia, Assoc Prof Goh said.

Then there is the fear that these surging costs and delays in the delivery of vital goods could add to global prices - just as inflation looked set to cool.

The knock-on implications for inflation will depend on how long the disruption persists and whether other shocks occur, experts said.

Nevertheless, observers told CNA that the disruption to global supply chains may not be as bad as during the pandemic, when trade came to a near-standstill amid prolonged city lockdowns and port closures.

Also, unlike the Suez Canal blockage in 2021, Mr Mc Garry stressed that the Red Sea and the Suez Canal were not entirely shut off at the moment.

Roughly 20 per cent of large cargo traffic has been diverted away from the Red Sea, he said. This comprises mainly large shipping liners, but smaller shippers have chosen to stay the course for reasons such as competition for business.

“I think it’s worth putting that into perspective and for that reason, it’s why we are not seeing the impact yet,” said Mr Mc Garry.

“If it was as bad as some of the media headlines are saying, then we will be feeling it in the supermarkets now. But we are not.”

A broader risk is the possible eruption of another geopolitical flashpoint and a shock to the world economy.

“Beyond the shipping realm, we are looking at a broader global geopolitical picture that’s just getting worse and worse,” said Mr Mc Garry. “What’s happening in the Red Sea right now is just another crisis on top of more crises.”

For small and open economies like Singapore, an increasingly fragmented world can only be bad news.

“The rules-based global order that Singapore has benefited from is seeing cracks everywhere. The ability to move goods seamlessly between borders is starting to crack. We saw that in the pandemic but now we're seeing it in terms of economic and trade restrictions between various nations,” Mr Mc Garry said.

“That just impacts the ability of a country like Singapore to fluidly do business.”

What’s it like for businesses in Singapore?

Singapore-based shipping company Pacific International Lines (PIL) said it is continuing with its Red Sea services for now, such as to ports in Yemen and East Africa, “while taking enhanced security measures and keeping in constant contact” with its vessels in the region.

“While we make every effort to minimise disruptions to our services, the situation is fluid. Our utmost priority is on the safety of our crew, and we are monitoring the developments closely,” said Captain Abhishek Chawla, PIL’s general manager of operations and procurement.

AOCL’s Ms Kaur anticipated that the following weeks would likely remain a “tense” period, with freight forwarders like her having to keep a close watch on rate increases and last-minute route diversions; and work out alternative plans for clients.

The attack on Singapore-flagged Maersk Hangzhou last weekend, for example, was “a shocker” and led to a “mad scramble”, with the shipping giant's subsequent decision to pause all sailings through the Red Sea producing complications for her chemical cargo.

“We survived what happened during the pandemic, then we got the Suez Canal incident which we also breezed through. But now we have another new situation, it's really difficult for the maritime industry,” said Ms Kaur.

Beyond shipping businesses, some food importers in Singapore are also working out alternatives to counter shipment delays, while balancing costs.

X-Inc, which runs food distributors FoodXervices and GroXers, has been informed that its shipments from Europe will take “another three to four weeks longer”, and with additional costs.

“As we might not have enough stocks, we would have to purchase locally where the cost is higher, and that’s if (there are) enough stocks locally,” said X-Inc's chief executive Nichol Ng.

“We have also tried to hold some stock buffer, but there is nothing much we can do especially if this situation pops up last minute.”

Bublik, a grocery that imports food from Central and Eastern Europe, said part of its fresh produce like fruits and dairy products are being brought in by air.

Its sea shipments have not been impacted by delays so far, but it will have to contend with these issues moving forward.

“We have been advised by our logistics company that the rates for the Red Sea route have gone up by more than 50 per cent,” said its owner Anna Jaeger.

“For our next sea shipments, we will either have to face these higher costs, or it could be an alternative to take a ship with a routing around Africa instead, resulting in a longer shipment time.”

What will it take to resolve the situation?

For now, it seems that most parties involved in the Red Sea tensions have been "rational, not wanting the war to escalate”, said Assoc Prof Goh from NUS.

As long as this remains the case, the situation will be kept under control and within current boundaries, though it "may not be easy to find mutually acceptable solutions given that positions have been entrenched over the years", he added.

Mr Mc Garry pointed out that the majority of Houthi attacks thus far have been swiftly intercepted by US forces. “If the US navy weren't there, this would be a much worse situation.”

The set-up of Operation Prosperity Guardian also provided some assurance but public details of its plans to protect the seaway remain scant.

“The French navy is there. The UK navy is there. The US navy is there. But they are all doing their own thing. It would be better if they could do it in an organised way," said Mr Mc Garry.

"That would send a very strong message to the shipping community that we are here to defend you.

“Then, it’s a question of the resolve of the Houthi movement. What are they willing to do? What are the tactics and weapons that the Houthi rebels have at their disposal?” he added.

“But they don't seem to show any sign of stopping what they are doing, unless there's concession from Israel in Gaza. Again, that's a million-dollar question which no one can answer.”