Squeezed by inflation and low salaries, Taiwan’s young adults see their dreams fading

One graduate spends almost a third of his salary renting a 72-sq-ft room. One observer says some Taiwanese youths can afford a home only if they ‘don’t eat or drink’ for 20 years. Why are some in Taiwan ‘stuck’?

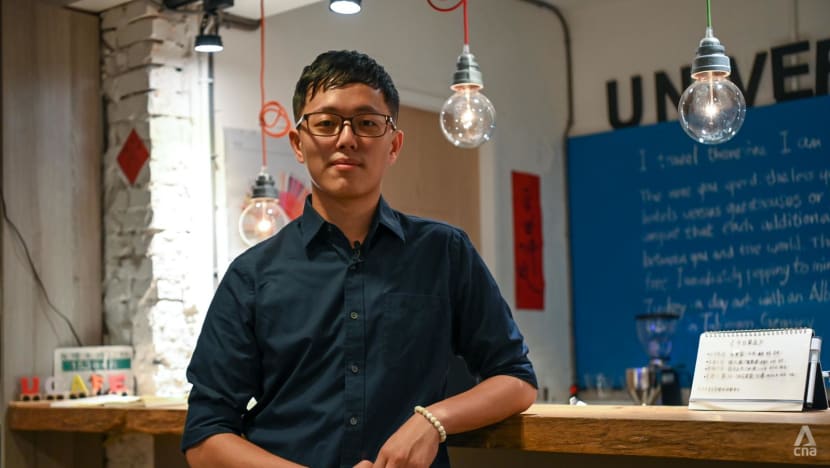

Adriel Wang has dreamt of making films since he was young. As he tries to make ends meet in Taiwan now, his reality is very different. (Photo: Tan Wen Lin/CNA)

- Despite going to university, many young Taiwanese are worse off than their parents were after entering the workforce.

- They are faced with the realities of living on stagnant wages and paying high rents, especially in Taipei.

- One graduate has got multiple jobs just to cope, though for many like him, the issues arise earlier: When choosing what to study.

- Even as the future may seem bleak for some young people, there are those hoping to spur change.

TAIPEI: Since young, Adriel Wang has dreamt of working in the film industry.

He remembers watching the film Jurassic Park as a child and being fascinated by the special effects and technology used to bring the prehistoric creatures to life.

“It convinced me that dinosaurs really looked like that,” said the 25-year-old. “It was so magical to me … I wanted to do the same thing.”

It is a dream he still thinks about as he rides his motorcycle past the cinema, looking up at the brightly lit film posters. But it is a far cry from his reality of delivering food on the UberEats platform.

Wang graduated with a broadcasting degree from a Taiwanese university in 2021 and works as a video producer for a start-up media platform.

But with his monthly salary at NT$32,000 (S$1,350), he has had to take on multiple jobs. Besides delivering food ad hoc, Wang works part-time as a dishwasher in a restaurant and does translation work for a television series.

“All I do is earn as much money as possible to make ends meet,” he said.

His dream has been put on hold for now. “I want to make movies and touch people’s hearts,” he said wistfully. “But I’m not sure I’ll ever achieve my dream.

“I’m still contemplating whether or not to give up on it.”

Wang is not alone in finding things hard after graduation. Nearly 54 per cent of Taiwan’s population aged 25 to 34 has a degree, according to statistics from the Ministry of the Interior.

In the United States, it is 51 per cent, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data. The OECD average is 47 per cent.

With more graduates comes more competition for jobs. And for young people like Wang, a degree is not the golden ticket it used to be. With wages stagnating and the cost of living spiralling in recent years, some of them struggle to get by, let alone build a future or chase their dreams.

‘GOLDEN ERA’ OVER

The rapid economic development Taiwan experienced from the 1960s led to the territory being named one of the four Asian Tigers.

At its peak in the 1980s, the economy grew by 14.25 per cent, according to Taiwan’s National Statistics. From 1978 to 1988, the average annual wage growth rate was over 12 per cent, said Lee Chien-hung, a professor in the Chinese Culture University’s department of labour and human resources.

“I refer to this as the golden era of wage growth in Taiwan’s post-war history,” he said.

That was when the parents of today’s young adults came of age and entered the workforce.

But the current generation faces a different economic environment and labour market from before, Lee said. According to official statistics, over the past 10 years, Taiwan has seen single-digit growth. This year, growth is projected to dip to 2.04 per cent.

At the same time, there is an oversupply of college graduates. Societal pressure is the reason that more young Taiwanese are pursuing higher education, said Hung Ching-shu, a research director of non-governmental organisation Taiwan Labour Front.

“There was an era when having higher education led to stable employment and a higher income. And this value was prevalent in most families, leading them to aspire to better education for their children,” he said.

The educational system also offered relatively accessible entry to university, which made obtaining a degree less challenging.

According to statistics from Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, the number of universities has increased from 57 in the 2001 academic year to 126 in the 2021 academic year.

“It seems (to employers) that there’ll be people to take up the job even if they offer low pay,” said Liu Mei-chun, the chair of the National Chengchi University’s Graduate Institute of Labour Research. “As a result, there’s no pressure to (offer) better pay.”

WATCH: Stuck with low pay, how Taiwan’s young graduates cope with high costs | Asia’s stuck generation (24:49)

She remembers her shock when one of her graduating students told her the monthly salary he was offered as an editor was just over NT$20,000.

“I felt a deep sense of frustration,” she said. “How can someone survive in Taipei with that salary?

“Many parents often say, ‘I sent you to university, but after graduation, your salary is even lower than what I earned with a high school diploma.’”

In the case of Wang, it was also “really difficult” to find a job after graduation. “In the job market for the visual media industry, the demand for talent is low,” he said.

He had two choices: Stay in the industry — which he described as more aligned to his passion — or look for roles only “somewhat related” to what he wanted to do. He ended up in a media start-up, where his job scope includes writing proposals, managing events and dealing with marketing strategies.

“If I’d chosen to work in (visual) media only, the starting salary was … only NT$26,000,” he said. “The difference between these two options, especially when I was in need of money, made me think about which was most suitable.”

Even so, his current salary has forced him to supplement his income by working side gigs. Besides his living expenses, Wang has student loans and a loan from a friend to repay.

To save money, he continues to live with his parents in Taoyuan and commutes to Taipei daily. Enduring the commute, more than an hour each way, saves him almost NT$3,000 a month — a tidy sum, given that almost 30 per cent of his salary goes towards repaying his loans.

“Do I feel more tired than others? Yes,” he said. “But it’s the choice I made.”

EXPECTATIONS VERSUS REALITY

Besides a low starting salary, however, fresh graduates may have to grapple with wages remaining low even after a few years.

It took 30-year-old Kao Min-ru four years to throw in the towel as an engineer in a global bicycle company. At that point, she was earning NT$32,000 monthly, which was NT$5,000 more than her starting salary as a fresh graduate.

Kao graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering relating to the traditional heavy industries commonly found in Taiwan.

She had gone into engineering thinking her future would be “very stable and promising”. She had imagined that she would climb the career ladder in her company, get married, have children and retire at the age of 60.

But reality proved otherwise. Despite trying to improve her English in corporate writing and spoken skills, she did not see a significant jump in her salary — “it increased by maybe NT$1,000 or NT$2,000 each year”.

“I’d been working in this company for four years, but my salary hadn’t reached NT$40,000,” she said. “It made me wonder — after working so hard, I was still stuck at the same level.

I made an effort to study hard and become what (society) wanted, … go to university and follow the conventional path of work. … But I didn’t become the person I wanted to be.”

According to information from the Ministry of Economic Affairs, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) employed 9.2 million people in 2021, representing more than 80 per cent of the total workforce.

But these SMEs may not be inclined to invest in their workers.

A 2018 article in the Taiwan Business Topics magazine, citing the National Development Council’s studies, reported a high correlation between company size and salary: The median monthly salary of a listed company was NT$51,000 in 2015, while the figure for non-listed companies was NT$33,000.

Furthermore, the median monthly salary was less than NT$30,000 in companies with fewer than 10 employees, and over NT$40,000 in companies with more than 100 workers.

Besides, many of these SMEs tend to be family-owned, which means high-level positions tend to stay within the family, said Hung. “If you hold a middle management position, you still won’t have the opportunity to gain ownership.”

This had been a frustration to Kao, who said: “I couldn’t see significant opportunities for career advancement.”

While she acknowledged that she could have gone to a larger company or to Taiwan’s high-performing technology industry, where salaries are higher, she said her peers who did so often have to work long hours.

“They’ve saved money, but they also tell me their lives aren’t enjoyable,” she said. “They come home at 7 p.m. or 8 p.m., scroll on their phones, watch TV and then go to bed. I don’t think that’s what I want.”

Hung also pointed to another issue: That students do not adequately consider their job prospects when choosing their field of study at university.

“Without a clear sense of their interests, they may choose a field that’s popular or perceived as interesting by others,” he said. “After investing four years and a considerable amount of effort, they may realise that the industry isn’t as promising as they initially thought, or the job isn’t what they expected.”

This was the situation Xu Cheng-rui, 32, found himself in after he graduated in 2014 with a degree in Chinese literature.

“I chose the Chinese department because I had a strong interest in language and literature. But I wasn’t clear about my future career path at that time,” he said. “After graduating, I realised that careers in language-related fields often had low starting salaries.”

This was something he also noticed about his peers, he said. “We tend to go with the flow and choose a major based on our academic performance at the time.”

His starting salary — in a broadcasting role in Kaohsiung — was around NT$21,000. He has since quit and works part-time as a server in a Japanese bar in Taipei while running a small fortune-telling business and selling crystals and his own handmade incense.

‘NORTH DRIFTERS’ FEEL THE SQUEEZE

Today, young Taiwanese also must grapple with inflation pushing up the cost of living.

According to the Labour Force Survey, the average salary for young workers aged 15 to 29 has increased by 24 per cent since 2012. But in June last year, the inflation rate also reached a 14-year-high, at 3.59 per cent.

“This situation is especially challenging for young graduates because their starting wages are already low,” said Lee. “But like other working individuals, they face the same inflation rate.

“I believe this is the most significant problem they’re currently facing.”

It is especially so for those who must deal with steep rents in a city like Taipei: the North Drifters, or “Bei Piao”.

They are young Taiwanese who have moved to Taipei to pursue higher education or better job prospects. The Storm Media reported last November that there are about 600,000 of them living in Taipei and New Taipei City.

Xu, who hails from Changhua, an agricultural county about one and a half hours away by train, is one of them. Realising that the prospects in his area, especially in the literary field, were limited, and the salaries less competitive, he decided to remain in Taipei after graduation.

Home for him is now a room in a shared flat. His room measures 72 square feet, or 6.7 square metres. It takes him five steps to walk from one end to the other.

“I chose this room because the rent was cheaper,” he said. Still, the rent is NT$11,000 every month, almost a third of his monthly earnings. This excludes utilities — another NT$3,000 or so.

It is small, he noted, and can feel a bit oppressive, but it is his safe harbour.

Nonetheless, when he talks to his parents about life in Taipei, he makes a point of showing them only photos of more spacious areas in the flat. “I share only positive updates,” he said.

He does not tell them about his income and that “life is so hard”. “I’m in my 30s,” he added. “I wouldn’t want to rely on them.

“When they see the photos, they’ll think that I’m doing quite well.”

Rents on homes along MRT lines in Taipei and New Taipei increased by about 30 per cent between 2010 and 2019, according to The Reporter in a 2021 report.

Andy Chang, 28, chief executive officer of Taiwanese non-profit Believe In Next Generation, contrasted this with salaries for youths, which increased by less than 16 per cent.

“If Taiwanese youths don’t eat or drink for 20 years, then they can afford a home,” he said. “But will housing prices still be the same in 20 years?”

Indeed, for Kao, who currently lives in Taichung, buying a home of her own is out of the question for now. She once dreamt of owning a three-bedroom flat and would view houses in the evenings after work.

But after doing her sums, she realised that even with a monthly salary of NT$40,000, it would not be affordable. “Apartments that are three or four decades old still cost around NT$5 million to NT$6 million,” she cited.

Mortgage payments would leave her with NT$15,000 a month. “How can I sustain my life with that amount? It’s practically impossible,” she said.

“Even if I save money diligently for 10 years, I wouldn’t be able to accumulate such a substantial amount.”

WHAT IS PLAN B?

Kao has now started her own business, helping foreigners relocating to Taiwan to settle in. She helps them with anything from finding a place to rent, buying furniture to handling paperwork such as residency permits and banking matters.

“If you need help and there’s no one to assist you, I’ll be there,” she said. She had lived in Canada for a year after graduation, and the locals helped her settle in. It gave her the idea of doing the same for foreigners in Taiwan who cannot speak Mandarin.

To boost her earning power, she is diversifying her professional skill set: She has obtained a real estate licence and is working on getting a licence to handle insurance for her customers.

“Starting a business may not initially bring in a lot of money, but I’ll face it head on and overcome the obstacles,” she said. “Eventually, I’ll get to buy my own home.”

Fellow Taiwanese Chang Yun-jhen, meanwhile, has set her sights on moving overseas. The 33-year-old worked in a travel agency after graduation, earning about NT$20,000 monthly. But it “wasn’t something (she) enjoyed”.

Then she moved to Singapore and worked in food and beverage (F&B) for four years. “The salary was better than in Taiwan: about S$2,300,” she said. After two years in Singapore, she was able to pay off her student loan.

Back in Taiwan now, she has two part-time jobs, one as a member of the kitchen staff in a Japanese hotpot restaurant and the other as a retail salesperson.

“It’s too difficult to earn a decent living in Taiwan,” she said. “I’ve been working for 16 years since high school, and I’m still in the same situation.”

In the long term, her goal is to gain certification in eldercare and go overseas as a healthcare worker. She is open to other F&B jobs overseas, however, should the opportunity come along.

“It’s quite common,” she said about her desire to leave. “I already have three or four friends … who are working overseas and have no plans to return.

If you have certain skills and can earn more money by working overseas, why not?”

Indeed, according to Taiwan’s National Statistics, the number of Taiwanese working overseas increased by 77,000 between 1998 and 2019, at an average annual growth rate of 1.1 per cent.

That includes youths, said Liu, who encourages her students not to limit themselves to Taiwan’s job market.

“I tell them to develop strong language skills while in university,” she said. “Taiwanese students are generally hard-working. And in many foreign countries, we can have a competitive advantage in the job market if language isn’t a significant barrier.”

A PROJECT FOR CHANGE

While the future in Taiwan may look bleak for some young people, there are those who hope to spur change — such as Andy Chang the non-profit CEO, who has seen first-hand the housing challenges his peers have faced in Taipei.

“There were rooms with kitchen conversions or toilet conversions on balconies,” he said, speaking of his shock at some of the rental listings he has come across. He has seen rooms with no windows and subdivided flats with wooden boards serving as partitions.

A decade ago, a private room with an en-suite bathroom could rent for NT$10,000 a month, he said. But rent for a bedroom in the city centre has since gone up to NT$17,000.

“When young people come here, they often have high hopes,” he said. “They believe the city will provide a stage for them to pursue their dreams.

“But many of them end up disappointed.”

During the pandemic, when many people started working from home, he and his team developed a youth apartment project.

He realised there were 190,000 underutilised residential units in Greater Taipei, most of them unoccupied. His organisation now matches landlords of these properties with North Drifters looking for rentals, makes the units liveable and subsidises a quarter of the rent.

Then renters are encouraged to “give back positively to society”, that is, to work on a project benefiting the community.

“Our goal is to provide them with a liveable and affordable space where they can then channel their creativity and talent into positive social change,” he said. “It’s important for them to feel a sense of fulfilment.”

One beneficiary is Tseng Chih-wei, 31, who lives with three others in an art-themed flat in the centre of Taipei.

Tseng, who is an actor, director, screenwriter and dancer, used to live in a small, windowless room. “It was quite depressing without sunlight,” he said.

Now he has a room in the youth apartment, with its spacious living room and kitchen, his mental and physical health has improved, he said. As all his flatmates are in arts-related fields, they have bonded well and have even considered opportunities for collaboration.

“It gives me a creative space; (it’s) not just about financial assistance,” he said.

For his community project, Tseng has opened his living space to conduct workshops helping those living with Aids to express themselves.

Since 2021, Believe In Next Generation has set up seven youth apartments, with about 40 residents in total.

“It may not be much compared to the 600,000 North Drifters,” said Andy Chang. “You might say we’re just a drop … in the ocean, and a drop of water in a vast ocean might not be important.”

“But right now we’re like a drop of water in the desert.

This is our home, so I want to take matters into my own hands and solve the problems here.”

SETTING YOUTHS ON THE RIGHT JOB PATH

There are also ways of mitigating the job situation, highlighted the experts who spoke to CNA Insider.

Hung said the issue of youngsters not considering their job prospects carefully enough when choosing what to study can be addressed by giving them early insights into professions and industries.

Most Taiwanese families, he said, tend to expect their children to enter university immediately after graduating from high school. He suggested that students could enter the workforce for a short while before going to university, to gain practical work experience.

“They can explore different career paths and discover areas of interest and potential for growth,” he said. “Once they have a clearer sense of their career direction, they can return to school.”

At the university level, Liu said existing internship programmes may vary in quality.

Students can be required, for example, to pay for the privilege of doing an internship. There have been media reports, on the other hand, of internships turning into forced labour for foreign students, prompting Indonesia to freeze recruitment in 2019 for a university internship programme in Taiwan.

“Taiwan lacks a screening mechanism, leading to inconsistent internship experiences,” said Liu. “In the long run, this can result in wasted time and money for students who gain little from their internships.”

Hence, she recommended that the Taiwanese government screen companies involved in internship programmes. She also suggested that the government step in to penalise companies that reap huge profits but pay their workers poorly.

The government has made money available for young people.

In 2019, the Executive Yuan approved a four-year programme to invest in their careers. This programme enhances career guidance and preparation for employment and gives job placement assistance to students nearing graduation, among other initiatives.

The second phase of the programme, which targets those aged 15 to 29, was launched in May with NT$16 billion earmarked to help 800,000 youths obtain jobs over the next three years in key industries experiencing labour shortage.

In a statement then, the Ministry of Labour said the unemployment rate among those aged 15 to 29 was 8.38 per cent last year, “the lowest level since the financial crisis”, which ended in 2009. The first phase of the youth employment programme helped 750,000 youths to find jobs, the ministry added.

Challenges abound, but young people like Wang have resolved to remain positive.

He recently reminded himself of his dreams after rereading a high school essay he had written on how he would work hard, overcome challenges and eventually make it big in the film-making industry.

“Even though it may be tough, there’s a saying: There are many paths to a destination,” he said. “As long as I try hard every day, even though I may take a longer path, I’ll still succeed.”