She met over 100 guys but didn’t find love. In China, marriage is pie in the sky for many more

With the country’s marriage rate at an all-time low, the programme Insight explores the factors in play, from the changing attitudes of young Chinese to the cost of housing, and how authorities and parents are trying to reverse the trend.

As women in China move up in society, fewer of them are getting married. Finance executive Zhao Miaomiao is one of them, but not for lack of trying.

SHANGHAI: Last year, as her career took off following her move to Shanghai, China’s financial capital, finance executive Zhao Miaomiao felt it was time to look for a significant other.

So she went on a series of blind dates. Using a dating app, she met “quite a lot” of guys in person — more than 100 — within three to four months.

After they all struck out with her, she “realised that finding a partner is a really difficult task”.

“The first thing (guys) look at is whether the woman is attractive. And then they proceed to understand her personality and family background,” said the 28-year-old.

“However, … (women) prioritise the sincerity of the man. For example, they hope that the man who pursues them demonstrates effort and sincerity.”

Over in Beijing, media executive Liu Shutong has a boyfriend, but “it doesn’t matter” to her whether she gets married or not in future.

“First of all, what I want is to live in the present,” she declared. And that is a general attitude she sees among her peers.

“Nowadays, young people prioritise their current happiness, embracing a hedonistic lifestyle,” said the 24-year-old, who herself takes pleasure in ballet, yoga and shopping with friends. “We feel that … whether you choose marriage or not, you’re still happy.”

Whether by choice or otherwise, more young Chinese clearly are not getting married. In the past decade, the number of marriages has halved. Last year, 6.83 million couples tied the knot — an all-time low since records began in 1986.

Compared with Singapore, where 6.5 marriages per 1,000 residents were registered in 2021, the corresponding figure in China was 5.4 marriages per 1,000 people.

Among the urban youth, 44 per cent of Chinese women do not plan to marry, compared with nearly a quarter of the men, according to a 2021 survey conducted by the Communist Youth League.

While a decline in marriage has become a global phenomenon — almost 90 per cent of the world’s population live in countries with falling marriage rates — and the reasons can be complex, there are also particular factors in play in China.

The programme Insight finds out what is getting in the way of young Chinese finding love, and the different ways the authorities — and parents — are trying to reverse the trend.

A GROWING MISMATCH

One person who can offer an insight into why young Chinese are not coupling up is professional matchmaker Qian Lei, 27.

WATCH: Love(less) in China — Why aren’t young Chinese getting married? (45:53)

“In general, if a man tries to find a partner in the matchmaking market, he may say he doesn’t need a rich or beautiful woman, but he’s actually picky,” she said.

“He’s looking for someone who gives him a good first impression, and this is when he becomes more selective.”

As to why girls may reject a guy, it may be “because he doesn’t meet their height requirements”, said Qian. “Girls tend to value height a lot, and they often prefer guys who are at least 1.7 metres tall.”

Such eligibility “criteria” may seem superficial but are one aspect of the changing views on love and marriage in China.

The country’s rapid development has also created a mismatch between what men and women want in marriage, with China’s social conservatism at odds with decades of female empowerment.

“China’s transition from traditional to modern values has been very short. Other countries and regions may have taken 50 or 100 years, but we’ve experienced this phenomenon in just 20 to 30 years,” said sociologist Zhu Hong at Nanjing University.

Prior to 1999, when the government decided to expand the higher education system, women made up as little as 20 per cent of university admissions.

Female enrolment has since overtaken male enrolment at universities, hovering at 52 per cent for some years now. Accordingly, women’s economic independence has increased, and Mao Zedong’s famous phrase, “women hold up half the sky”, has become a reality.

But gender roles have not kept up with women’s socio-economic status — “all the housework” and the responsibility for child-rearing will fall mainly to them after marriage, said Jean Yeung, a Provost-Chair Professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore.

“The opportunity cost of getting married is really, really high for a woman these days. And so, since marriage is no longer a necessity, a lot of women hesitate to go in (on it).”

The difference between what men and women want is especially clear in the cities, added Hang Seng Bank (China) chief economist Wang Dan. “Most women are looking for love, and most men are looking for a wife.

“The difference in their purpose also causes a very different attitude. And we’ve seen a lot of frustration when it comes to closing the deal, on both sides, on whether they want to get married.”

More time spent at school and the focus on careers also mean a delay in marriage, which is common as countries develop.

But in China, this has led to the term “sheng nu” (leftover women), used to describe single women in their late 20s and 30s. They are deemed undesirable owing to fertility concerns over their age.

THE ONE-CHILD POLICY

China’s falling marriage rate could also be partly due to the one-child policy, which was implemented nationwide in 1980 and ended on Jan 1, 2016.

A whole generation of only children “grew up on their own”, noted Wang. “Naturally, they’re more individualistic than the previous generations.”

And according to one study by the Ohio State University, only children are less likely to get married, compared to those with siblings. Each additional sibling is associated with a 3 per cent increase in the odds of getting married.

The argument is that siblings provide children with opportunities to negotiate conflict at home, which could help in navigating friendships and romantic relationships later in life.

Only children are also likely to be more independent and value their alone time.

“To establish a marriage, they have to give up a bit of their individuality, a bit of their freedom. They also need to pay attention to the needs of their partner,” said Zhu.

But she doubts their ability to do so. “Being an only child is truly special. … Grandparents and other relatives revolve around the child. That’s why we call them ‘little sun,’” she said.

So all their needs are immediately met. … At the same time, their bad temper is tolerated.

“In this generation, when it comes to responsibility, selflessness and compromise, they may lack these social skills.”

They may find a partner “too bothersome” instead. “That’s why there are so many young people nowadays who have cats and dogs as pets,” she added.

THE ‘MOONLIGHT CLAN’

As they chase individual desires, a growing number of Chinese youths are now calling themselves the “Moonlight clan”, or “yue guang zu”. “It usually refers to young people (who’ll) spend everything they earn every month,” said Wang.

“Some of them are also deeply in debt because they now have access to online borrowing, (with) platforms like Alipay (and) JD Finance.”

One of the youths who identify as part of the Moonlight clan is Liu. She told Insight: “People who spend all their money each month consider it normal not to have savings. And they don’t save.”

Their live-for-today attitude leaves them ambivalent about the future. And as they delay financial security, they end up delaying marriage.

“If you’re someone who lives a ‘pay cheque to pay cheque’ lifestyle, your potential partner might realise it isn’t a good fit,” said Qian.

“In a way, it can be (a challenge) for a Moonlight clan person to find a partner. After all, building a life together involves managing finances.”

According to a China Central Television report in 2021, two in five singles in China’s first-tier cities belong to the Moonlight clan. In fourth- and fifth-tier cities, 76 per cent of single young people blow their pay cheque every month.

This adds up to a sizeable number, given that China had 220 million singles that year.

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT

China’s economic slowdown, coming hard on the heels of the pandemic, has compounded the situation. “Every time there are financial difficulties, the marriage rates are going to go down because people will usually delay these major life events,” said Yeung.

Unemployment among Chinese urbanites aged 16 to 24 stands at more than 20 per cent, which is a record and higher than in most European countries.

With the gloomy economic outlook, some men may be especially pessimistic about their marriage prospects.

“They may think, as a man, they need to take responsibility for their wife and … their children. Suddenly, they realise they don’t have the budget,” said Yeung.

In this regard, the cost of housing is “a big issue these days”. Studies have shown that when home prices go up, the number of marriages falls.

Even for Chinese youths who are “serious about their financial stability” and still thinking of marriage, “the ability to save up for a house, for their children’s education and all of that … isn’t there”, added Yeung.

China’s hustle culture known as “996” — which refers to working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. six days a week — has left young working adults, meanwhile, with hardly any time for themselves, much less the energy for a relationship.

“You do have to feel a bit more sympathetic (about) their status now,” said Wang. “The economic cost and the pressure to maintain a balanced life are just so high.”

‘SWIPE LEFT, SWIPE RIGHT’

Still, most Chinese youths have not given up on love. And many who are time-starved hope to get hitched with the help of dating apps.

The three most popular platforms, Momo, Soul and Tantan, have over 150 million monthly active users in total as at last year.

In a 2021 survey conducted by a Chinese research institute, 89 per cent of respondents said they had used a dating app before.

“You’ll see and hear examples of success. People do find long-term partners or even husbands and wives,” said Wang. “But most of the time, it’s more like a social app. People get together, become friends or establish some short-term relationships.”

There is also an argument that dating apps promote a hook-up culture, where users are interested in flings rather than something long-term. This has been Zhao’s experience, which led her to lament that guys “primarily consider” the sexual aspect.

She had thought using a dating app would be an efficient process because of the “large user base”. But the platform is not quite a godsend to the loveless in China.

“Dating apps give … the illusion that you’ll always have the next choice. Just swipe left, swipe right, then you’ll always have more choices down the line,” said Wang.

“It doesn’t necessarily create more happiness among couples or among the young generation. But I guess it’s one of these new realities that China as a whole has to (become) accustomed to.”

MATCHMAKING CORNERS

Even as dating apps have increased in popularity, there is a reason that traditional methods remain important in China.

“When you look at different surveys, the ways people meet a potential mate isn’t that different from 20 years ago. They still meet new people at work, through friends (and) through family,” cited Wang.

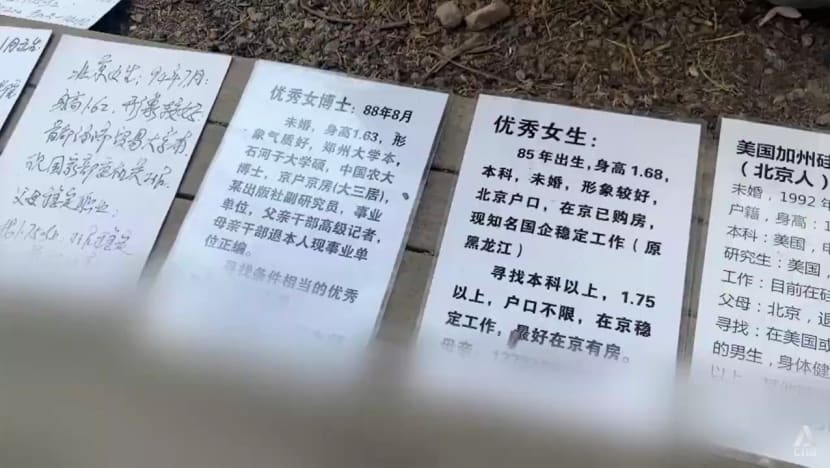

Parental matchmaking in particular has seen a revival since the mid-2000s, when worried parents with dreams of becoming grandparents began organising matchmaking corners in city parks.

Just like in a flea market, they advertised their children’s virtues, hoping to attract prospective takers.

“This trend still continues … because for many of the urban young generation, they don’t have enough time to really get into the dating market (through) trial and error, basically,” said Wang.

Matchmaking corners can be found in major Chinese cities, such as Guangzhou and Shanghai. In Beijing, one famous spot is Zhongshan Park, which artist Hao Wenxi, 35, knows well because his father used to frequent its matchmaking corner.

Hao shared that he had been looking for Miss Right since his early 20s but was unlucky in love for almost eight years. “I met a lot of different people, but the chances of success were relatively low,” he said.

“I didn’t know how to date. I didn’t know how to (be) charming and be emotionally present. I might’ve only known that I earn more than you. I own property.

“It was really no different to dating 100 years ago — saying that you have cows and land.”

But he wanted to find love, so he was game to try different dating options. He met around 20 to 30 people over a period of two to three years.

Dating apps yielded a mixed bag of results. Eventually, it was his father’s efforts in Zhongshan Park that paid off, and he met his current wife, a doctor. They dated for a year before tying the knot.

They now have a four-year-old son and are thinking of having another child, perhaps in the next three or four years.

EXTRA LEAVE AND OTHER NUDGES

Hao’s happy ever after highlights one particular dimension to China’s concern over its falling marriage rate: If people do not get married, they do not have children.

“The correlation between marriage and birth rates isn’t as strong (in Western society),” noted Wang. “People can still have children even if they aren’t married. … But in China, the correlation is almost 100 per cent.”

Besides conservatism, the Hukou system — the household registration system that allows citizens to access healthcare and education — is one big reason why. Until recently, only married women were allowed to register their children.

But last year, China’s population declined for the first time in six decades. And the falling marriage rate combined with an ageing population has the government fretting even more.

So authorities are trying various means to encourage marriage and childbirth, including efforts to control house prices.

By May last year, at least 13 Chinese cities were providing housing subsidies for families with multiple children. Local governments have also given one-time coupons to families for home purchases.

More subsidies and incentives, said Yeung, would help young people to think they could settle down. Zhu has some ideas, such as “marriage housing” specifically for young people, which she believes the government may introduce “in the near future”.

“If you’re willing to get married, then this house will be rented to you at a very low cost. If you’re willing to have children, perhaps this house will be sold to you at a very affordable price,” Zhu elaborated.

As for falling in love in the first place, some schools have given students extra vacation time to socialise, while some companies have offered single female employees extra days of annual leave, for them to “go home and date”.

Still, employees of enterprises in China are working, on average, 48.7 hours a week this year, even with the “996” work culture officially outlawed.

While China’s labour laws now require companies to pay extra for hours worked beyond an eight-hour working day, “when it comes to the execution stage, … the 996 culture is still quite prevalent”, said Wang.

“As a result, I think we’re now in this sort of … stalemate when it comes to the reality in dating.”

Many other Asian countries have tried ways to improve marriage rates, with more failures than successes. It remains to be seen whether China will buck the trend.

Zhao thinks it is “worth encouraging” youths who still believe in love. But for her part, she is having a break from the dating scene after using a matchmaker’s services on top of her use of dating apps.

“I want a high-quality marriage. But the people I currently know can’t meet my expectations. So even though they want to be with me, I still reject them,” she said.

“Being single is a good state for me right now. I enjoy my current single status, and I feel happy.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.

c659.jpg)